My Shopping Cart

My Shopping Cart

| Specification | Value |

|---|---|

| Product Name | PhozGuard 620 |

| Active Ingredients | Mono & Dipotassium Phosphonates (620 g/L equivalent phosphorous acid) |

| Mode of Action | Systemic fungicide activating plant immune responses and disrupting pathogen development |

| Target Diseases | Downy Mildew, Phytophthora and related oomycete pathogens |

| Base Material | Non-toxic potassium phosphite |

| Application | Foliar spray or soil application depending on crop and disease pressure |

| Chemical Compatibility | Mix-compatible with many agricultural pesticides |

| Regulatory Approval | APVMA Approval No. 66655/54106 |

| Sizes Available | 20 L, 200 L, 1000 L |

| Container Type | Dimensions (mm) | Weight | Pallet / Load Details | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 Litre Drum | 280 × 220 × 420 | 30 kg per drum | — | Used for smaller AgroBest product batches or specialty formulations. Compatible with standard freight and pallet shipments. |

| 200 Litre Drum (on Pallet) | Individual Drum: 590 × 590 × 920 Pallet Pack: 1200 × 1200 × 1050 |

260 kg total per pallet | 1–4 drums per pallet configuration | Ideal for bulk quantities of AgroBest crop nutrition or protection products. Provides safe, stable transport on standard pallets. |

| 1000 Litre IBC | 1200 × 1000 × 1160 | 1300 kg total | Forklift and pallet-jack compatible | Preferred for large-scale AgroBest liquid fertiliser, brine, or nutrient storage. Suitable for high-volume distribution. |

*All sizes and weights are approximate and may vary slightly depending on the specific AgroBest formulation and packaging batch.

| File | Title | File Description | Type | Section |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhozGuard_620_2022.pdf | PhozGuard 620 – Systemic Fungicide | PhozGuard 620 Safety Sheet | Specifications | Document |

Phytophthora root rot is a destructive soil-borne disease of olive trees caused by Phytophthora species (water-mould pathogens). At least seven Phytophthora species have been identified attacking olives in Australia . These pathogens infect roots and can extend into the lower trunk, causing root decay and crown cankers that girdle the tree. If left untreated, Phytophthora root rot can kill olive trees, either through a rapid collapse or a slow decline over several seasons . The disease has been observed in many olive-growing regions worldwide, often linked to periods of excessive soil moisture.

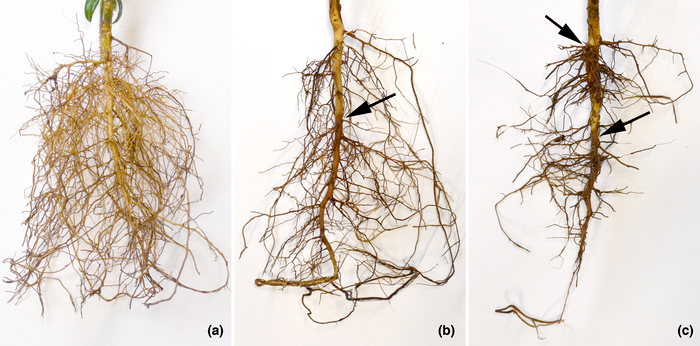

Symptoms: Infected olive trees typically show a loss of vigour and drought-like symptoms even when soil moisture is adequate. Foliage becomes sparse as leaves wilt, turn yellow, and drop prematurely . Shoot dieback starts at the tips of branches and progresses downward. In advanced cases, entire limbs or the whole canopy may wilt suddenly, especially under stress conditions like hot weather, flowering or heavy fruit load . Root and trunk symptoms include soft brown rot of feeder roots and lesion-like cankers at the crown or lower trunk; peeling back bark at the base often reveals reddish-brown discoloration of the wood. Affected trees may respond by shooting new suckers from the lower trunk or roots as the upper canopy dies back . Over time, the trunk can exhibit cracks or distortions due to the underlying canker damage . In some cases, trees can decline gradually over years, whereas in other cases they collapse quickly when the compromised root system can no longer support the canopy (for example, during a heatwave or late summer) .

Waterlogging and Poor Drainage: Excess soil moisture is the single biggest contributing factor to Phytophthora root rot in olives. Phytophthora thrives in saturated, oxygen-deprived soils. Australian conditions have consistently found Phytophthora outbreaks correlated with waterlogged conditions, claypan soil layers, or generally poor drainage in groves. Even a short period of waterlogging (as little as 24 hours) in warm temperatures can kill fine olive roots and predispose trees to infection. Low-lying orchard areas, heavy clay soils that drain slowly, or sites with a high water table create ideal conditions for the pathogen. It’s important to note that while waterlogging is a common trigger, Phytophthora can sometimes cause problems even in well-drained soils if the pathogen is present and environmental conditions (temperature, soil moisture) become favourable. In high-rainfall climates or during unusually wet seasons, otherwise well-drained olive blocks may still experience Phytophthora issues if drainage cannot keep up with prolonged rainfall.

Susceptible Rootstocks: Most olive trees in Australia are grown on their own root stock (i.e., not grafted), but in cases where different rootstocks or wild olive (Olea europaea subsp. africana) seedlings are used, susceptibility can vary. Caution is advised when using feral/wild olive trees as rootstocks or nursery stock. These plants can originate from areas where Phytophthora is present in the soil and may introduce the pathogen or be less tolerant to it. There is currently no widely available Phytophthora-resistant olive rootstock, so all varieties should be assumed susceptible. Research by Spooner-Hart et al. noted that the emergence of Phytophthora problems in Australian olives has coincided with the expansion of plantings into non-traditional (non-Mediterranean) climates and heavier soils. This underscores the role of environment and rootzone conditions in disease incidence.

Warm, High-Rainfall Climates: Olives are traditionally adapted to Mediterranean climates (winter rain, dry summers). In parts of Australia with warm temperatures and summer-dominant rainfall (e.g., coastal Queensland and northern New South Wales), the risk of Phytophthora root rot is higher. The pathogen is widespread in soils and waterways in these regions and can easily infect olive roots when wet, warm conditions persist. Growers in such climates must be especially proactive with prevention measures. High humidity and frequent rain not only favor the pathogen but can also mask early drought-stress symptoms - an infected tree might not show obvious distress until a dry period or heat event reveals the extent of root loss.

Disease Spread: Phytophthora produces motile spores (zoospores) that swim in free water, so the pathogen spreads with water movement through soil and runoff. It can be introduced or spread in a grove via infected nursery stock, contaminated soil on equipment, flood irrigation water, or even the boots of workers moving from an infested wet area to a clean area. Once in the soil, Phytophthora can persist for years in root debris or as resilient spores. Thus, any practice that moves soil or water (e.g., tractor(s) and farm equipment, drainage flows) from an infected zone to an uninfected zone can facilitate the dissemination of the disease. Growers should avoid transferring mud and material from known infested blocks and ensure any new trees planted are from disease-free sources (pathogen-free).

Successful management of Phytophthora root rot in olives relies on an integrated strategy. This includes preventative chemical treatments, supportive nutritional therapies, and cultural practices to improve soil conditions and reduce pathogen spread. The goal is to protect healthy roots from infection, eradicate or suppress the pathogen in soil where possible, and help affected trees recover. Below are the current industry best practice:

Phosphorous acid (also known as phosphonate or phosphite) is a key fungicide for mana PhozGuard 620 Phytophthora in many tree crops and is a cornerstone of preventative treatment in olives. Phosphonate does not act like a typical fungicide that directly kills the pathogen on contact, instead, it works by inhibiting Phytophthora growth and stimulating the tree’s own defense mechanisms. This dual mode of action makes it most effective as a preventative treatment, applied before or at the very early stages of infection, to help the plant resist invasion. Phosphorous acid is available under various trade names (e.g., Phosguard620) with different concentrations of active ingredient. Always confirm that the product is permitted for use on olives and follow the label or permit directions.

Application timing and rates: On woody perennial crops like olives, foliar sprays of phosphonate are typically applied approximately every 6 weeks during the growing season for ongoing protection. This ensures a consistent level of the fungicide within the plant, as it is systemic and will move into the roots. Label rates depend on product concentration; for example, products with around 600 g/L a.i. are used around 2.5 mL/L, 400 g/L formulations at 5 mL/L, and 200 g/L formulations at 10 mL/L (when applied with an air-blast sprayer to fully cover the foliage). For young or small olive trees, high-volume spraying to runoff ensures good coverage. Crucial timing is just before periods of high risk - e.g., before winter rains or summer wet spells - so that the roots are protected in advance.

In situations where an olive tree has very little foliage left (severe defoliation from root rot), phosphonate can be applied as a bark spray or trunk injection. Spraying a ~10% phosphorous acid solution directly on the trunk or injecting the solution into the lower trunk can deliver the fungicide to the vascular system when leaves are insufficient. Trunk application is usually done in autumn or spring when the tree is actively translocating, to maximise uptake. Always exercise caution with concentrated trunk sprays to avoid phytotoxicity and adhere to recommended concentrations carefully.

Mode of action and benefits: Once absorbed, phosphonate is translocated downward with the sap flow, reaching the roots and inhibiting Phytophthora in infected tissues. It also primes the tree’s immune response. Treated trees often show not only disease suppression but also improved new root development in some cases. Phosphonate is valued for being relatively inexpensive and having low toxicity to humans and non-target organisms, making it a practical choice for routine preventative use. In warm, high-rainfall regions of Australia where Phytophthora is endemic, applying phosphonate prophylactically to young olive trees can protect them until their root systems establish. Many agronomists recommend an initial phosphonate spray or injection soon after planting in such regions, followed by periodic treatments during the wet season.

It’s important to remember that phosphonate is a suppressive, not an eradicant, treatment. It significantly reduces Phytophthora levels and activity in the tree but does not eliminate the pathogen from the soil. Therefore, repetitive or at least annual reapplications are needed to maintain protection. If treatments are stopped, Phytophthora can rebound if conducive conditions return. Also, phosphonate works best on preventing new infections and halting early disease - severely diseased trees (with the majority of roots already rotted) may not recover with fungicide alone. In those cases, phosphonate can only prevent further spread while other measures support the tree’s regrowth.

Other fungicides: Another chemical option is metalaxyl-M (e.g., Ridomil Gold), a systemic fungicide specifically targeting oomycete pathogens like Phytophthora. Ridomil can be applied as a soil drench or via injection to kill Phytophthora in the root zone. It has shown effectiveness in olives, but similar to phosphonate, it does not sterilise the soil and must be reapplied periodically to keep the pathogen in check. Phosphonate is often preferred for long-term management due to lower cost and resistance risk, but Ridomil drenches can be useful as a curative kick-start in heavily infested soils or to protect newly planted high-value trees. Always rotate or mix chemical modes of action as allowed, to prevent the development of fungicide resistance in the Phytophthora population.

As an example for conventional application... Calcium nitrate at 10 g/L plus Solubor (boron) at 1.5 g/L, mixed in water, applied as a fine foliar spray every 6 - 8 weeks. Calcium nitrate provides a readily absorbed form of calcium (along with some nitrogen to spur growth), and Solubor is a common soluble borate fertiliser that assists to correct boron deficiency. These can be tank-mixed and sprayed to cover the foliage; ideally, apply in the cooler part of the day (morning or late afternoon) to reduce the risk of leaf burn. Liquid boron applications like Agrodex Boron are usually recommended.

In addition to fungicides, nutritional support plays a critical role in managing Phytophthora root rot - especially for helping infected trees recover. Two nutrients in particular, calcium (Ca) and boron (B), have been observed to assist olive trees suffering from root rot. Calcium and boron are closely associated with the growth of new shoots and root tips; they are essential for cell wall strength (Ca) and cell division/floral development (B). Some olive varieties have relatively high requirements for Ca and B compared to other fruit trees, and deficiencies of these nutrients often manifest as dieback of shoot tips (boron deficiency can cause tip death and poor new leaf growth, while calcium deficiency leads to weak stems and twig dieback).

When roots are compromised by Phytophthora, the tree’s ability to uptake nutrients from the soil is severely impaired. Ailing roots mean even if fertilisers are in the soil, the tree may still suffer from nutrient deficiencies. Foliar feeding can bypass the damaged root system and deliver nutrients directly to the leaves and young shoots. Foliar sprays of calcium and boron have shown positive results in reducing twig dieback and stimulating new growth on moderately affected olive trees. The recommended practice (from field experience in Australia) is to apply calcium and boron together on a regular schedule during the active growing season:

It’s worth noting that while calcium and boron are the focus for tip dieback, other nutrients should not be neglected. Trees battling root rot might also benefit from magnesium (for chlorophyll), zinc (for hormone production), and other micronutrients if deficient. However, over-applying any one element can cause imbalances or toxicity (boron, for instance, can be toxic above recommended rates). Stick to label rates and recommended concentrations for all foliar feeds, and monitor leaf nutrient levels if possible. The Ca+B foliar program should be seen as one component of a broader nutritional management plan for stressed trees. Start with Soil and/or Leaf Analysis to ascertain data from your grove.

Beyond calcium and boron, a complete foliar nutrient program is advised for olive trees with significantly impaired root systems. Because root rot limits uptake of both macro- and micro-nutrients, foliar applications of a balanced fertiliser can supply the tree with essential nutrients until roots recover. Many agricultural suppliers offer soluble foliar fertiliser blends (NPK plus Trace Elements) that can be sprayed on the canopy. These blends often contain nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, as well as micronutrient like zinc, manganese, iron, copper, molybdenum, etc., in plant-available forms. Applying such a foliar feed can green up a chlorotic, declining tree and promote new leaf and root development while bypassing the diseased root system.

A suggested regimen is to spray a complete foliar fertiliser (for example, an NPK 20-20-20 with trace elements, or a product formulated for orchard foliar feeding) on a monthly or bi-monthly schedule during the growing season. This can often be done in conjunction with the calcium nitrate and boron sprays - either by alternating them or, if compatibility is confirmed, combining them in one tank mix. Be cautious when mixing fertilisers with fungicides: phosphonate is generally compatible with many fertilisers, but always jar-test combinations or consult product labels.

Foliar nutrient programs should be tailored to the grove’s specific deficiencies. If leaf analysis or visual symptoms indicate particular nutrient shortages (e.g., yellowing between veins might indicate magnesium or iron deficiency, small, distorted new leaves could indicate zinc deficiency), include or emphasise those nutrients in the foliar mix. Maintaining good overall nutrition will improve the tree’s resilience. Stronger, well-nourished olive trees have a better chance to compartmentalise Phytophthora infections and resume normal growth once conditions improve. Remember that these sprays supplement but do not replace soil fertilisation; once roots recover function, reinstating a normal soil fertiliser program (adjusted for any residual soil fertility and the tree’s regained capacity) is important for long-term production.

Cultural controls that improve the soil environment are fundamental to managing Phytophthora - no chemical or nutrient can fully substitute for a well-drained root zone. Growers should evaluate their grove for any conditions that contribute to waterlogging or poor root health and take corrective action:

Both phosphonate fungicides and calcium-boron foliar feeds are important tools in managing Phytophthora root rot, but they serve different purposes and have distinct advantages and limitations. It’s not an either/or choice - in fact, they are complementary in a comprehensive management program. Below is a comparison to clarify their roles for growers:

It’s also worth comparing phosphonate with the other fungicide option, metalaxyl (Ridomil). Phosphonate and Ridomil both suppress Phytophthora, but in different ways. Ridomil is more of a curative, directly toxic to the pathogen, whereas phosphonate has those immune-boosting properties. Ridomil can knock back an active infection faster, but it has a higher cost and a risk of resistance development in the pathogen population with overuse. In practice, phosphonate is often used for regular protection, and Ridomil (if used at all) might be reserved for spot-treating severe cases or as a pre-plant soil drench in known infested sites. Both chemicals require reapplication; neither provides permanent protection. Always follow an Integrated Disease Management philosophy when using these tools - they are most effective when combined with the cultural and nutritional strategies described above.

Managing Phytophthora root rot requires an Integrated Disease Management approach, especially in Australia’s warm, high-rainfall olive-growing regions. No single intervention is a silver bullet; instead, growers should implement a suite of preventive and remedial measures that together minimise disease impact. Below is a summary of IDM practices for Phytophthora root rot in olives:

Managing Phytophthora root rot in olives is challenging, but with vigilant management, it is possible to minimise losses and even restore affected groves to health. The keys are prevention (through site selection, drainage, and preventative fungicides) and support (through nutrition and careful cultural care for stressed trees). Australian olive growers should view Phytophthora management as an ongoing part of grove management, much like pruning or pest control, especially in regions prone to heavy rainfall. By implementing the integrated strategies outlined above, growers can significantly reduce the impact of Phytophthora root rot, protecting their trees and investment. Remember that every grove is different - monitor your olive trees closely and adapt these recommendations to local conditions, and always reference current guidelines from olive industry research and local agricultural authorities. With a proactive, informed approach, even the threat of “root rot” can be managed, and olive trees can continue to thrive and produce in the Australian landscape.