My Shopping Cart

My Shopping Cart

AgroDex BORON is a concentrated liquid boron fertiliser designed to rapidly correct boron deficiencies in a wide range of crops. Complexed with organic acids, it delivers superior plant uptake and mobility, ensuring boron reaches the tissues where it is most needed. Boron is essential for cell division, flowering, pollination, seed formation, and fruit set, and it also plays a vital role in calcium uptake and water regulation. AgroDex BORON supports healthier plants, better reproductive growth, and higher quality produce.

AgroDex BORON is used to correct boron deficiencies and promote healthy flowering, pollination, fruit and seed set, and reproductive development. It is suitable for broadacre crops, cotton, vegetables, stonefruit, pome fruit, nuts, olives, grape vines, sub-tropical crops, and turf. It can be applied through both foliar spraying and fertigation systems.

| Nitrogen (as Primary Amine) | 4.5% w/v (3.5% w/w) |

| Boron (as Aminoethyl Ester Complex) | 10% w/v (7.7% w/w) |

| Biostimulants (as Organic Acids) | 2% w/v (1.5% w/w) |

| Colour | Dark Brown |

| S.G. | 1.28 - 1.32 |

| pH | 7.5 - 8.5 |

| Pack Sizes | 20 Litre, 200 Litre, 1000 Litre |

| Crop | Rate/Ha | Dilution | Application Timing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broadacre / Cotton | 1 - 3 L | 1:50 | Apply at early flowering and seed set |

| Vegetables | 2 - 4 L | 1:100 | Apply as required |

| Stonefruit / Pome | 1 - 3 L | 1:100 | At leaf emergence and early flowering, with follow-ups as required |

| Nuts / Olives | 1 - 2 L | 1:100 | Apply pre-flowering and again after fruit set |

| Sub-Tropicals | 2 - 4 L | 1:200 | Apply at bud development, early flush, and set |

| Grape Vines | 1 - 3 L | 1:100 | Apply pre- and post-flowering |

| Turf | 200 mL / 100 m² | 1:100 | As required to correct deficiencies |

| General Volume Rate | 500 mL / 100 L | - | Spray volume x 0.5% product (500 mL per 100 L water) |

What happens to crops when boron deficiency is not corrected?

When crops lack boron, cell division and reproductive processes are impaired. This can result in poor pollination, reduced fruit set, deformed fruit, and weak seed formation. Boron deficiency also limits calcium uptake, leading to weaker plant tissues and reduced water regulation. AgroDex BORON quickly corrects these deficiencies, ensuring healthy flowering, fruiting, and high-quality yields.

Key benefits include:

This makes AgroDex BORON an essential trace element fertiliser for growers aiming to maintain healthy crops and high production.

20 Litre Drum

Dimensions: 280 x 220 x 420 mm

Weight: 30 kg per drum

Notes: Commonly used for smaller batches of olive processing liquids or specialty products. Compatible with most small freight consignments and pallet loads.

200 Litre Drum (on Pallet)

Individual Drum Dimensions: 590 x 590 x 920 mm

Pallet Pack Dimensions: 1200 x 1200 x 1050 mm

Pallet Weight: 260 kg total

Load Size: Same pallet configuration for 1 to 4 drums

Notes: Ideal for bulk olive oil or processing aids. Secured on a standard pallet for improved stability during transport.

1000 Litre IBC (Intermediate Bulk Container)

Dimensions: 1200 x 1000 x 1160 mm

Weight: 1300 kg

Notes: A popular format for large-scale olive oil storage, brine solutions, or wastewater collection. Compatible with forklift and pallet-jack handling.

| File | Title | File Description | Type | Section |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agrodex_Boron_2022_safety_data.pdf | AgroDex BORON | Agrodex BORON is a high analysis Boron formulated to rapidly correct deficiencies in all crops. Agrodex Boron is complexed with organic compounds, which assist the plant in uptake and mobilisation. | Catalogue | Document |

A successful Grove Management Plan must cover these key areas:

"A grove without an effective irrigation system is unlikely to deliver consistent yields year after year. Many growers still underestimate the water needs of olive trees, and few actually monitor soil moisture levels. This is why so many groves have never achieved a commercial crop." Marcelo Berlanda Specialist Olive Consultant

Water stress negatively affects flowering, fruit set, oil accumulation (oil production), fruit size (table olives), fruit quality, and overall tree health. However, many growers lack a proper system to monitor soil moisture or manage irrigation effectively.

Marcelo recommends:

"Growers should inspect soil moisture weekly during spring and summer, and every two weeks in autumn and winter. Use a shovel to dig at least 400mm under the tree canopy to check moisture. If the soil is hard to dig, it’s too dry – even if the canopy shows no visible signs of stress."

Advanced soil moisture monitoring tools can also provide reliable data on a digital display or computer dashboard.

For optimal grove health, growers must consistently check soil moisture and prevent water stress.

As discussed previously, taking leaf samples is essential to assess your trees’ nutritional status. This information guides the creation of a fertiliser program, a critical component for boosting or maintaining yields.

Typically, no fertiliser is needed in winter, unless you’re addressing soil amendments. However, some groves have severe nutrient deficiencies requiring fertiliser even in winter. Where proper irrigation systems aren’t in place, growers must broadcast fertiliser before rain to allow rainfall to incorporate nutrients into the soil profile, an inefficient use of resources but often the only option.

When applying fertiliser in these conditions, target the area beneath the canopy and, if possible, cultivate the soil to improve incorporation and reduce product loss.

Olives need four essential nutrients: Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Potassium, and Calcium. Check product labels carefully. As a general guideline, aim for:

Avoid pruning during the coldest part of winter and when it’s wet or foggy to reduce the risk of bacterial and fungal disease spread.

The main goals of pruning are to remove dead wood, reduce canopy size, restore tree balance, encourage healthy new growth, and increase fruit set in spring.

Tip: After pruning, apply a copper-based spray to protect wounds from infection by fungi and bacteria.

Pest & disease management is crucial for sustaining yield and tree health. Winter’s colder temperatures reduce insect activity, offering a prime time to tackle pest issues.

Set up a comprehensive Pest and Disease Monitoring Program. During winter, check marked trees (previously affected by pests or diseases) every two weeks; in spring, check weekly. Look under leaves and on new growth for signs like crawlers, yellow spots, black sooty mold, or anything unusual.

Proactive, weekly management is essential for a successful grove.

If you need further assistance, please contact us.

URGENT FERTILISER SUPPLY UPDATE – MAP & DAP SHORTAGE

This summer cropping season is facing unprecedented challenges in fertiliser supply. Availability of MAP fertiliser (monoammonium phosphate) and DAP fertiliser (diammonium phosphate) is expected to remain extremely limited worldwide, with serious implications for growers planning their nutrient programs.

Since 2021, China has imposed strict quotas and inspection rules on phosphate fertiliser exports to protect domestic prices and safeguard food security.

The impact has been dramatic:

Although Morocco, Russia, the USA, and Saudi Arabia also produce MAP and DAP, they cannot offset the sharp drop in Chinese exports.

The result is:

For olive growers and other professional producers, the impacts are already being felt:

Do not wait for traditional ordering windows. Place orders immediately and consider forward contracting for next season. Securing current pricing now helps protect your operation against higher costs and potential shortages later.

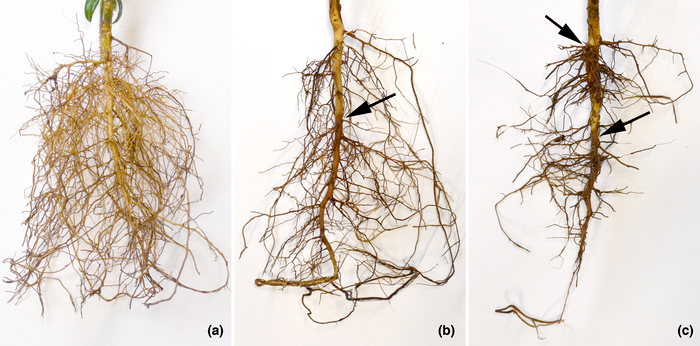

Phytophthora root rot is a destructive soil-borne disease of olive trees caused by Phytophthora species (water-mould pathogens). At least seven Phytophthora species have been identified attacking olives in Australia . These pathogens infect roots and can extend into the lower trunk, causing root decay and crown cankers that girdle the tree. If left untreated, Phytophthora root rot can kill olive trees, either through a rapid collapse or a slow decline over several seasons . The disease has been observed in many olive-growing regions worldwide, often linked to periods of excessive soil moisture.

Symptoms: Infected olive trees typically show a loss of vigour and drought-like symptoms even when soil moisture is adequate. Foliage becomes sparse as leaves wilt, turn yellow, and drop prematurely . Shoot dieback starts at the tips of branches and progresses downward. In advanced cases, entire limbs or the whole canopy may wilt suddenly, especially under stress conditions like hot weather, flowering or heavy fruit load . Root and trunk symptoms include soft brown rot of feeder roots and lesion-like cankers at the crown or lower trunk; peeling back bark at the base often reveals reddish-brown discoloration of the wood. Affected trees may respond by shooting new suckers from the lower trunk or roots as the upper canopy dies back . Over time, the trunk can exhibit cracks or distortions due to the underlying canker damage . In some cases, trees can decline gradually over years, whereas in other cases they collapse quickly when the compromised root system can no longer support the canopy (for example, during a heatwave or late summer) .

Waterlogging and Poor Drainage: Excess soil moisture is the single biggest contributing factor to Phytophthora root rot in olives. Phytophthora thrives in saturated, oxygen-deprived soils. Australian conditions have consistently found Phytophthora outbreaks correlated with waterlogged conditions, claypan soil layers, or generally poor drainage in groves. Even a short period of waterlogging (as little as 24 hours) in warm temperatures can kill fine olive roots and predispose trees to infection. Low-lying orchard areas, heavy clay soils that drain slowly, or sites with a high water table create ideal conditions for the pathogen. It’s important to note that while waterlogging is a common trigger, Phytophthora can sometimes cause problems even in well-drained soils if the pathogen is present and environmental conditions (temperature, soil moisture) become favourable. In high-rainfall climates or during unusually wet seasons, otherwise well-drained olive blocks may still experience Phytophthora issues if drainage cannot keep up with prolonged rainfall.

Susceptible Rootstocks: Most olive trees in Australia are grown on their own root stock (i.e., not grafted), but in cases where different rootstocks or wild olive (Olea europaea subsp. africana) seedlings are used, susceptibility can vary. Caution is advised when using feral/wild olive trees as rootstocks or nursery stock. These plants can originate from areas where Phytophthora is present in the soil and may introduce the pathogen or be less tolerant to it. There is currently no widely available Phytophthora-resistant olive rootstock, so all varieties should be assumed susceptible. Research by Spooner-Hart et al. noted that the emergence of Phytophthora problems in Australian olives has coincided with the expansion of plantings into non-traditional (non-Mediterranean) climates and heavier soils. This underscores the role of environment and rootzone conditions in disease incidence.

Warm, High-Rainfall Climates: Olives are traditionally adapted to Mediterranean climates (winter rain, dry summers). In parts of Australia with warm temperatures and summer-dominant rainfall (e.g., coastal Queensland and northern New South Wales), the risk of Phytophthora root rot is higher. The pathogen is widespread in soils and waterways in these regions and can easily infect olive roots when wet, warm conditions persist. Growers in such climates must be especially proactive with prevention measures. High humidity and frequent rain not only favor the pathogen but can also mask early drought-stress symptoms - an infected tree might not show obvious distress until a dry period or heat event reveals the extent of root loss.

Disease Spread: Phytophthora produces motile spores (zoospores) that swim in free water, so the pathogen spreads with water movement through soil and runoff. It can be introduced or spread in a grove via infected nursery stock, contaminated soil on equipment, flood irrigation water, or even the boots of workers moving from an infested wet area to a clean area. Once in the soil, Phytophthora can persist for years in root debris or as resilient spores. Thus, any practice that moves soil or water (e.g., tractor(s) and farm equipment, drainage flows) from an infected zone to an uninfected zone can facilitate the dissemination of the disease. Growers should avoid transferring mud and material from known infested blocks and ensure any new trees planted are from disease-free sources (pathogen-free).

Successful management of Phytophthora root rot in olives relies on an integrated strategy. This includes preventative chemical treatments, supportive nutritional therapies, and cultural practices to improve soil conditions and reduce pathogen spread. The goal is to protect healthy roots from infection, eradicate or suppress the pathogen in soil where possible, and help affected trees recover. Below are the current industry best practice:

Phosphorous acid (also known as phosphonate or phosphite) is a key fungicide for mana PhozGuard 620 Phytophthora in many tree crops and is a cornerstone of preventative treatment in olives. Phosphonate does not act like a typical fungicide that directly kills the pathogen on contact, instead, it works by inhibiting Phytophthora growth and stimulating the tree’s own defense mechanisms. This dual mode of action makes it most effective as a preventative treatment, applied before or at the very early stages of infection, to help the plant resist invasion. Phosphorous acid is available under various trade names (e.g., Phosguard620) with different concentrations of active ingredient. Always confirm that the product is permitted for use on olives and follow the label or permit directions.

Application timing and rates: On woody perennial crops like olives, foliar sprays of phosphonate are typically applied approximately every 6 weeks during the growing season for ongoing protection. This ensures a consistent level of the fungicide within the plant, as it is systemic and will move into the roots. Label rates depend on product concentration; for example, products with around 600 g/L a.i. are used around 2.5 mL/L, 400 g/L formulations at 5 mL/L, and 200 g/L formulations at 10 mL/L (when applied with an air-blast sprayer to fully cover the foliage). For young or small olive trees, high-volume spraying to runoff ensures good coverage. Crucial timing is just before periods of high risk - e.g., before winter rains or summer wet spells - so that the roots are protected in advance.

In situations where an olive tree has very little foliage left (severe defoliation from root rot), phosphonate can be applied as a bark spray or trunk injection. Spraying a ~10% phosphorous acid solution directly on the trunk or injecting the solution into the lower trunk can deliver the fungicide to the vascular system when leaves are insufficient. Trunk application is usually done in autumn or spring when the tree is actively translocating, to maximise uptake. Always exercise caution with concentrated trunk sprays to avoid phytotoxicity and adhere to recommended concentrations carefully.

Mode of action and benefits: Once absorbed, phosphonate is translocated downward with the sap flow, reaching the roots and inhibiting Phytophthora in infected tissues. It also primes the tree’s immune response. Treated trees often show not only disease suppression but also improved new root development in some cases. Phosphonate is valued for being relatively inexpensive and having low toxicity to humans and non-target organisms, making it a practical choice for routine preventative use. In warm, high-rainfall regions of Australia where Phytophthora is endemic, applying phosphonate prophylactically to young olive trees can protect them until their root systems establish. Many agronomists recommend an initial phosphonate spray or injection soon after planting in such regions, followed by periodic treatments during the wet season.

It’s important to remember that phosphonate is a suppressive, not an eradicant, treatment. It significantly reduces Phytophthora levels and activity in the tree but does not eliminate the pathogen from the soil. Therefore, repetitive or at least annual reapplications are needed to maintain protection. If treatments are stopped, Phytophthora can rebound if conducive conditions return. Also, phosphonate works best on preventing new infections and halting early disease - severely diseased trees (with the majority of roots already rotted) may not recover with fungicide alone. In those cases, phosphonate can only prevent further spread while other measures support the tree’s regrowth.

Other fungicides: Another chemical option is metalaxyl-M (e.g., Ridomil Gold), a systemic fungicide specifically targeting oomycete pathogens like Phytophthora. Ridomil can be applied as a soil drench or via injection to kill Phytophthora in the root zone. It has shown effectiveness in olives, but similar to phosphonate, it does not sterilise the soil and must be reapplied periodically to keep the pathogen in check. Phosphonate is often preferred for long-term management due to lower cost and resistance risk, but Ridomil drenches can be useful as a curative kick-start in heavily infested soils or to protect newly planted high-value trees. Always rotate or mix chemical modes of action as allowed, to prevent the development of fungicide resistance in the Phytophthora population.

As an example for conventional application... Calcium nitrate at 10 g/L plus Solubor (boron) at 1.5 g/L, mixed in water, applied as a fine foliar spray every 6 - 8 weeks. Calcium nitrate provides a readily absorbed form of calcium (along with some nitrogen to spur growth), and Solubor is a common soluble borate fertiliser that assists to correct boron deficiency. These can be tank-mixed and sprayed to cover the foliage; ideally, apply in the cooler part of the day (morning or late afternoon) to reduce the risk of leaf burn. Liquid boron applications like Agrodex Boron are usually recommended.

In addition to fungicides, nutritional support plays a critical role in managing Phytophthora root rot - especially for helping infected trees recover. Two nutrients in particular, calcium (Ca) and boron (B), have been observed to assist olive trees suffering from root rot. Calcium and boron are closely associated with the growth of new shoots and root tips; they are essential for cell wall strength (Ca) and cell division/floral development (B). Some olive varieties have relatively high requirements for Ca and B compared to other fruit trees, and deficiencies of these nutrients often manifest as dieback of shoot tips (boron deficiency can cause tip death and poor new leaf growth, while calcium deficiency leads to weak stems and twig dieback).

When roots are compromised by Phytophthora, the tree’s ability to uptake nutrients from the soil is severely impaired. Ailing roots mean even if fertilisers are in the soil, the tree may still suffer from nutrient deficiencies. Foliar feeding can bypass the damaged root system and deliver nutrients directly to the leaves and young shoots. Foliar sprays of calcium and boron have shown positive results in reducing twig dieback and stimulating new growth on moderately affected olive trees. The recommended practice (from field experience in Australia) is to apply calcium and boron together on a regular schedule during the active growing season:

It’s worth noting that while calcium and boron are the focus for tip dieback, other nutrients should not be neglected. Trees battling root rot might also benefit from magnesium (for chlorophyll), zinc (for hormone production), and other micronutrients if deficient. However, over-applying any one element can cause imbalances or toxicity (boron, for instance, can be toxic above recommended rates). Stick to label rates and recommended concentrations for all foliar feeds, and monitor leaf nutrient levels if possible. The Ca+B foliar program should be seen as one component of a broader nutritional management plan for stressed trees. Start with Soil and/or Leaf Analysis to ascertain data from your grove.

Beyond calcium and boron, a complete foliar nutrient program is advised for olive trees with significantly impaired root systems. Because root rot limits uptake of both macro- and micro-nutrients, foliar applications of a balanced fertiliser can supply the tree with essential nutrients until roots recover. Many agricultural suppliers offer soluble foliar fertiliser blends (NPK plus Trace Elements) that can be sprayed on the canopy. These blends often contain nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, as well as micronutrient like zinc, manganese, iron, copper, molybdenum, etc., in plant-available forms. Applying such a foliar feed can green up a chlorotic, declining tree and promote new leaf and root development while bypassing the diseased root system.

A suggested regimen is to spray a complete foliar fertiliser (for example, an NPK 20-20-20 with trace elements, or a product formulated for orchard foliar feeding) on a monthly or bi-monthly schedule during the growing season. This can often be done in conjunction with the calcium nitrate and boron sprays - either by alternating them or, if compatibility is confirmed, combining them in one tank mix. Be cautious when mixing fertilisers with fungicides: phosphonate is generally compatible with many fertilisers, but always jar-test combinations or consult product labels.

Foliar nutrient programs should be tailored to the grove’s specific deficiencies. If leaf analysis or visual symptoms indicate particular nutrient shortages (e.g., yellowing between veins might indicate magnesium or iron deficiency, small, distorted new leaves could indicate zinc deficiency), include or emphasise those nutrients in the foliar mix. Maintaining good overall nutrition will improve the tree’s resilience. Stronger, well-nourished olive trees have a better chance to compartmentalise Phytophthora infections and resume normal growth once conditions improve. Remember that these sprays supplement but do not replace soil fertilisation; once roots recover function, reinstating a normal soil fertiliser program (adjusted for any residual soil fertility and the tree’s regained capacity) is important for long-term production.

Cultural controls that improve the soil environment are fundamental to managing Phytophthora - no chemical or nutrient can fully substitute for a well-drained root zone. Growers should evaluate their grove for any conditions that contribute to waterlogging or poor root health and take corrective action:

Both phosphonate fungicides and calcium-boron foliar feeds are important tools in managing Phytophthora root rot, but they serve different purposes and have distinct advantages and limitations. It’s not an either/or choice - in fact, they are complementary in a comprehensive management program. Below is a comparison to clarify their roles for growers:

It’s also worth comparing phosphonate with the other fungicide option, metalaxyl (Ridomil). Phosphonate and Ridomil both suppress Phytophthora, but in different ways. Ridomil is more of a curative, directly toxic to the pathogen, whereas phosphonate has those immune-boosting properties. Ridomil can knock back an active infection faster, but it has a higher cost and a risk of resistance development in the pathogen population with overuse. In practice, phosphonate is often used for regular protection, and Ridomil (if used at all) might be reserved for spot-treating severe cases or as a pre-plant soil drench in known infested sites. Both chemicals require reapplication; neither provides permanent protection. Always follow an Integrated Disease Management philosophy when using these tools - they are most effective when combined with the cultural and nutritional strategies described above.

Managing Phytophthora root rot requires an Integrated Disease Management approach, especially in Australia’s warm, high-rainfall olive-growing regions. No single intervention is a silver bullet; instead, growers should implement a suite of preventive and remedial measures that together minimise disease impact. Below is a summary of IDM practices for Phytophthora root rot in olives:

Managing Phytophthora root rot in olives is challenging, but with vigilant management, it is possible to minimise losses and even restore affected groves to health. The keys are prevention (through site selection, drainage, and preventative fungicides) and support (through nutrition and careful cultural care for stressed trees). Australian olive growers should view Phytophthora management as an ongoing part of grove management, much like pruning or pest control, especially in regions prone to heavy rainfall. By implementing the integrated strategies outlined above, growers can significantly reduce the impact of Phytophthora root rot, protecting their trees and investment. Remember that every grove is different - monitor your olive trees closely and adapt these recommendations to local conditions, and always reference current guidelines from olive industry research and local agricultural authorities. With a proactive, informed approach, even the threat of “root rot” can be managed, and olive trees can continue to thrive and produce in the Australian landscape.

AgroBest is an Australian manufacturer with a wide range of crop protection and liquid fertiliser products to help keep your olive trees healthy and productive. This guide gives you a practical overview of the AgroBest range available through The Olive Centre and how they can fit into your nutritional grove program across the season. We’ll walk through foliar feeds, soil conditioners, pest and disease support products, spray adjuvants and biostimulants, explaining when to use, and how to help with common olive problems. Whether you’re dealing with nutritional needs or tired trees that just aren’t performing, this guide is designed to help you quickly match the right AgroBest product to the needs of your grove. A soil and leaf analysis are recommended to narrow down the correct product(s).

Foliar nutrition is critical for addressing immediate nutrient needs and boosting olive tree productivity. AgroBest offers several NPK foliar fertilisers and trace element sprays designed for quick uptake through leaves. These products provide balanced macronutrients (nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium) often enhanced with micronutrients or biostimulants to improve efficacy.

Healthy soil is the foundation of productive olive groves. AgroBest offers products that improve soil fertility, structure, and microbiology - ensuring roots have access to nutrients and water. These soil conditioners and granular/liquid fertilisers are applied to the soil (via drench, fertigation, or banding) rather than sprayed on foliage.

Using these soil-oriented products, olive growers can address issues like poor soil fertility, low organic matter, or imbalanced nutrients in the root zone. For instance, if an olive grove is suffering from nutrient lock-up or weak root growth, a combination of humic-enriched Kickstart and organic GroMate can rebuild soil life. If soil calcium or pH is an issue, products like CarboCal can supply calcium in a plant-accessible form that strengthens soil and trees alike. Healthier soil translates to stronger, more resilient olive trees with better uptake of nutrients and water.

While AgroBest’s focus is on nutrition, some of its products also play a role in crop protection - either by directly deterring stresses or by strengthening the plant against pests and diseases. Olive growers face challenges such as black scale insects, fungal diseases like peacock spot and anthracnose, as well as environmental stresses (frost, heat) that can predispose trees to problems. AgroBest products can be part of an integrated strategy to tackle these issues.

It’s important to note that AgroBest does not produce synthetic pesticides or fungicides - instead, their offerings focus on prevention and plant strength. For active infestations like a severe black scale attack or an anthracnose epidemic, growers would still use specific registered pesticides (e.g. a petroleum spray or an IGR for scale, or a copper fungicide for anthracnose/fungal issue). However, integrating AgroBest products could mean fewer such interventions are needed. By using nutritionals and protectants like Envy and Spraytech Oil proactively, olive growers can reduce stress and pest pressure on their groves. This integrated approach leads to a more sustainable pest and disease management, leveraging plant health to fight off challenges naturally. Always test product compatibility before mixing.

Adjuvants are “helper” products that improve the performance of agrochemical sprays - ensuring that nutrients or pesticides stick as intended. AgroBest’s adjuvants are especially valuable in olive production, where the undersides of leaves and the waxy surfaces of olive foliage can make spray coverage difficult. Using the right adjuvant means more of your spray actually reaches the target and stays there, rather than bouncing off or drifting away. Two key adjuvant products in the AgroBest range are:

AgroBest AgroChelate - An organic acid concentrate used as a water conditioner, compatibility agent, and nutrient uptake enhancer. Agro “Chelate” is essentially a blend of organic acids and amino acids. When added to a spray tank or fertigation system, it acidifies the solution slightly (bringing pH to a plant-friendly level), chelates micronutrients (preventing them from reacting with other chemicals or getting locked up), and improves the mixing of otherwise incompatible inputs. For example, olive growers often want to tank-mix calcium with phosphorus fertilisers or combine multiple trace elements - this can cause precipitation or antagonism. AgroBest’s Chelate product helps keep such mixes stable and ensures the nutrients remain in a form the plant can absorb. It also acts as a mild biostimulant due to its amino acid content, so foliar feeds with AgroChelate might show improved uptake into leaves. In summary, Agro Chelate is used as an adjuvant to condition spray water (especially if it’s alkaline or hard), to prevent clogging and leaf burn, and to facilitate smooth absorption of nutrients through the leaf cuticle. It’s particularly useful in foliar trace element programs and fertigation systems. (Available in liquid form; e.g. 5L and 20L containers.)

Using adjuvants like these is highly recommended in olive spray programs. Olives have small, waxy leaves and a dense canopy; getting sprays to penetrate and stick can be challenging. By using Spraytech OIL, growers report more uniform coverage and better results from both pest control and foliar feeding efforts (the improved uptake means you might achieve desired results with lower application rates, saving cost). Similarly, with AgroBest’s chelating adjuvant, complex tank mixes become more stable - meaning you can, for instance, mix your zinc, boron, and magnesium foliar feeds with confidence that each will remain available to the tree. In sum, AgroBest adjuvants ensure you get the maximum benefit from every spray, an important consideration given the time and cost involved in spraying an olive grove.

Biostimulants are products that don’t fit the traditional “fertiliser” mould of simply providing N-P-K, but instead contain natural compounds (like seaweed extracts, humic acids, beneficial microbes, etc.) that enhance plant growth and resilience. AgroBest has embraced this technology by offering several biostimulant products that can give olive trees an extra edge - improving root growth, boosting stress tolerance, and increasing nutrient uptake efficiency. These are especially relevant to olives, which often face stresses like drought, high salinity, and poor soils.

By integrating biostimulants into their regime, olive growers can tackle challenges like nutrient-poor soils, irregular bearing, or climate stress in a more natural way. For example, facing a scenario of “off-year” in an alternate-bearing olive grove, one might apply SeaFil or Fulfil to reinvigorate the trees and potentially improve the next bloom. In drought-prone areas or saline irrigation conditions, biostimulants help olive trees maintain growth and yield where they otherwise might suffer. These products do not replace standard NPK fertilisers but rather supplement the nutrition program by ensuring that the plant can make the most of nutrients and overcome growth hurdles. They are akin to vitamins and probiotics for your olive trees - not absolutely required, but when used properly, they often lead to healthier, more productive plants.

Product Sizes & Usage Note: Most AgroBest biostimulants are available in various sizes to suit different scales of operation - from 1-5 L bottles for small groves up to 200 L drums for large farms. They are generally applied at low concentrations (e.g. a few litres per hectare as a foliar spray). It’s important to follow recommended timing - many biostimulants show best results when applied at specific growth stages (like root flush, pre-flowering, or stress events).

In Australian agriculture, understanding the hidden nutrients in your soil and plants can make the difference between an average harvest and a thriving one. Leaf and soil analysis give farmers, agronomists, olive growers, and even hobby gardeners a scientific window into their crops’ health. By regularly testing both the soil and the leaves (foliage) of your olive trees or other plants, you gain precise data to fine-tune fertiliser use, correct deficiencies, and boost overall productivity. The result is healthier olive groves, higher yields of quality fruit, and more sustainable soil management - an investment that pays off in both the short and long term through improved crop performance and soil health.

In Summary, AgroBest’s range of products on The Olive Centre spans everything from core fertilisers to innovative biostimulants, all geared toward improving plant nutrition and resilience. By grouping products into foliar feeds, soil conditioners, protection aids, adjuvants, and biostimulants, we see that each category addresses different aspects of olive grove management:

Sources: The information in this article is from The Olive Centre’s product listings and knowledge base, including technical descriptions of AgroBest products and their recommended uses. Each product mentioned is available through The Olive Centre; for detailed application rates and guidelines, please refer to the specific product pages and labels. By reviewing these resources and field experiences, we’ve provided an integrated overview to help you make informed decisions about which AgroBest products can best address the needs of your olive grove.

Marcelo Berlanda’s “Pruning for Production” guide highlighted why olive pruning is vital to sustain yields. This article builds on that foundation, focusing on how to encourage the growth of productive fruiting wood in Australian olive groves.

Olive trees bear fruit on one-year-old shoots – the growth produced in the previous season. Ensuring a steady supply of these young, fruitful shoots each year is critical for consistent yields. Without renewal, canopies fill with aging wood that carries fewer leaves and buds, leading to lower productivity. Pruning is therefore geared toward a few fundamental objectives :

Understanding how and when olive fruiting buds form helps refine pruning practices. Unlike deciduous fruit trees, olives do not have a true winter dormancy – their buds remain in a state of quiescence and will grow when conditions permit. Flower buds initiate relatively late: studies have shown that olive buds begin differentiating into inflorescences about 2 months before bloom (around late winter/early spring in the local climate). This means the buds on this year’s spring flowering shoots were formed in the late summer or autumn of last year, on the previous year’s wood. Crucially, those buds needed sufficient resources and light while they were forming.

Several physiological factors influence fruitful bud development:

Takeaway: Productive fruiting wood arises from a balance – neither too vegetative nor too weak – and it needs sunlight. Pruning is the tool to create that balance by removing what’s unproductive and making space for fruitful shoots under the right environmental conditions.

Having set the physiological context, we now turn to pruning methods that encourage renewal of fruiting wood. The approach will vary with the age of the tree and the orchard system (traditional vs. high-density), but several general principles apply:

By applying these pruning techniques, growers encourage a continuous supply of young fruiting wood while avoiding the pitfalls of over-pruning. The result is a tree that renews itself gradually: always plenty of 1-year shoots ready for the next crop, and no big shocks to the tree’s system.

Olive orchards in Australia range from traditional low-density plantings to modern high-density (HD) and super-high-density (SHD) groves. The principles of fruiting wood renewal apply to all, but the methods and intensity of pruning are adjusted to each system’s needs :

In summary, the pruning strategy must fit the system: gentle but regular for intensive hedges, somewhat heavier but less frequent for large traditional trees, and always aimed at keeping enough young wood in the pipeline. Regardless of system, the fundamentals remain: capture sunlight, encourage new shoots, and remove what’s unproductive.

Pruning not only influences yields – it also plays a significant role in Integrated Pest and Disease Management (IPDM). A well-pruned olive canopy is generally healthier and easier to protect. Here’s how encouraging productive wood ties in with pest and disease considerations:

In summary, a sound pruning regimen is a cornerstone of IPM in olives. It reduces pest and disease pressure naturally by altering the micro-environment and improving the efficacy of other controls. Always balance the need for opening the canopy with the tree’s productive capacity – a healthy medium density (not too sparse) is the target, so that you don’t invite sunscald or stress. With those caveats, pruning is one of the most cost-effective pest management tools a grower has.

Beyond pruning itself, several environmental and cultural factors influence how well an olive tree can produce new, fruitful wood. Understanding these helps growers create conditions that favour the continual renewal of fruiting shoots:

In summary, productive fruiting wood is not just about cutting branches – it’s the outcome of the whole orchard management system. Pruning is the mechanical stimulus, but water, nutrients, and overall tree stress levels determine how the tree responds. The best results come when pruning is synced with these factors: prune to shape the growth, irrigate and fertilise to support it (but not overdo it), and protect the tree from stresses that could derail the process. By doing so, growers in Australia can maintain olive canopies that are youthful, vigorous, and laden with fruitful shoots year after year.

Encouraging productive fruiting wood in olives is both an art and a science. The art lies in “reading” the tree – knowing which branches to remove and which to spare – while the science lies in understanding olive physiology and applying evidence-based practices. In this follow-up to Marcelo Berlanda’s pruning guide, we have underlined the key strategies:

Sources: This article integrates findings from peer-reviewed studies and reputable industry publications, including research by Gómez-del-Campo et al. on light and yield distribution, Tombesi and Connor on pruning and olive physiology, Rousseaux et al. on bud dormancy and flowering, and Australian olive industry resources (NSW DPI, AOA IPDM manual) on best practices. These sources reinforce the recommendations above and ensure advice is aligned with the latest understanding of olive tree management.