| File | Title | File Description | Type | Section |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polaris_Edible_Lines_Catalogue.pdf | Polaris Automazioni Edible Bottling Lines Catalogue | Catalogue | Document | |

| POLARIS_Spirits_Catalogue.pdf | Polaris Automazioni Spirit Bottling Lines | Catalogue | Document |

In a Pickle!

The following pickling recipes article has been adapted from

Australian Olive Grower Issue 4, November 1997

______________________________________

Chapters

Lost Arts

Pickling in Yesteryear

Favourite Greek pickling method

Pickling in Peasant Style

Ash and olives

______________________________________

No doubt, she then took some home to her humble abode and, to her even greater delight, was able to duplicate the process. People still cure olives today in some Greek islands by dipping a basket of olives daily into the sea for 10 days. When the inner flesh is dark brown, the olives are ready to eat.

To begin the brine processing, place your clean olives in cold water and change the water each day for 10 days. (I use large, plastic, covered buckets from a local restaurant supply.) Weight the olives down with a plate so they all stay submerged. No need to seal at this point.

This will start leaching the bitter glucosides out of the olives. At the end of the ten day period you can make a more permanent brine solution in which to continue the process. Add one cup of noniodized salt to each gallon of water. Use enough of this brine to cover the olives.

Change this solution weekly for four weeks, transfer the olives to a weaker brine solution until you are ready to use them. The solution should contain one half cup of noniodized salt to each gallon (4.2 litres) of water.

Just how long it will take for your olives to become edible I cannot say. Mine seem to take about two or three months to develop a rich, olivey flavour. The best piece of equipment you have for assessing when the olives are done is located between your nose and your chin. It doesn't cost much to maintain (outside of your regular dental checkups), so use it!

Store your olives in the weaker brine in a fairly cool, dark place and keep them covered. A scum may form on the top of the olives, but according to my mother's Italian neighbours, this simply adds to the flavour of the olives! (One of my Italian sources swears that this is the "culture which consumes the bitterness of the olives.") Toss out the scum and use any olives that look unspoiled. (A squishy olive is a spoiled olive.)

Editor's note: Using the pickling method outlined above, and the complete absence of salt during the initial ten day rinsing period, bacteria can form and turn the fruit soft and rotten during the following weeks. If this happens, you will lose your entire production. Experiment with it, use about 5% salt solution for one batch and no salt for another batch. To care for the environment, there are some commercial methods that do not use the daily rinse method.

Pickling in Yesteryear Back to top

The following five recipes come from the Beaumont Nursery Catalogue of many years ago. The Brock family who operated the nursery have since moved on, but Beaumont House, which was taken over by the National Trust in about 1976, is very much a landmark today. Beaumont House was Sir Samuel Davenport's original home in the 1850's.

The nursery catalogue claims that the first olive trees imported to Australia were shipped by Sir Samuel Davenport and planted on his Beaumont property in 1844. Our thanks go to the Brock family for the years they spent in developing the Australian Olive Industry.

"It is a very simple matter to pickle olives and all you need is a small wooden vat or barrel or an earthenware jar with an open top similar to a glazed bread crock, and if you are interested the following recipes may be of some assistance to you:

Referring to all the following recipes, it is essential that when pickling, the olives must not be bruised in any way. Fruit must be picked just as the olive is turning colour from green, that is when it shows a small patch of pinkish purple and is commencing to soften. Always cover the containers to exclude all light.

No. 1 Recipe. Place olives carefully in container, cover the olives with a caustic soda solution (3 oz. of caustic soda to 1 gallon rainwater) for 40 to 48 hours (no longer), using a piece of flat, clean wood to keep them below the surface of the liquid. At the end of 48 hours pour off the caustic liquid, then cover with fresh rainwater and continue the renewing and pouring off of the water twice daily, night and morning, for at least one week (until all caustic soda is eliminated.) Do not worry if olive is bitter to taste.

Next, mix well 1/2 lb. of salt to one gallon of rainwater and cover the olives in this solution for a week, then drain. You then mix 3/4 lb. salt (12 oz.) to each gallon of rainwater, cover for another week and drain again. You then place the olives into jars. A-Gee jars or similar. Place jars in tub of very hot water up to their necks and fill with a boiling brine solution (3/4 lb/ salt to one gallon of water) to overflowing and seal immediately. As the jars cool the rubber rings will seal the tin inner lids perfectly and the olives will keep indefinitely.

Recipe No 2. Place olives in vat and cover with a caustic soda solution (1 lb. caustic soda to five gallons of rainwater). Allow to stand for 18 to 20 hours, then pour off the dark brown liquid. Keep washing in rainwater until the water comes away clear, changing the water each day. This will take seven or eight days. Then bottle the olives in A-Gee jars or other suitable containers. Stand jars in tub of very hot water up to their necks and then pour boiling brine solution over olives to overflowing and seal immediately. This brine to be one cup of salt to 12 cups of rainwater.

Recipe No 3. (for green olives). Dissolve 1 lb. caustic soda in five gallons of water. Pour over the olives and let stand for 15 hours. Drain this off and cover the olives with clear, cold water, and when this becomes discoloured pour it off. Continue in this way until water remains clear. Pack the olives into jars and cover then with a strong solution of salt & water (one part of salt to five parts of water), which has previously been boiled for 10 minutes, then seal.

Recipe No 4. (green olives). 3 ozs. of caustic soda dissolved in one gallon cold rainwater (glass or stone or wood containers) in sufficient quantity to cover the olives to be processed.

Important: Cover to exclude all light. Cover olives with this solution, according to size of olives, 20 to 24 hours. Then wash with running water for at least 3 days (exclude all light) and drain then. Add a prepared solution of 1/2 lb salt per gallon of water and change every day for at least 12 days. Then drain, bottle and cover with a fixing solution of brine, 3/4 lb salt to one gallon of water (use coarse salt. "from the butchers".)

Recipe No 5. (Our experience of this recipe is that the olives do not keep more than a few months). Place olives in container of wood, glass or earthenware and cover with a solution of caustic soda, 5 dessert spoons to one gallon of water, for 48 hours. Then pour off and keep washing in pure cold rainwater until water is clear and natural (change water each day). Then place in jar and cover with brine solution (1 1/2 lb. salt to each gallon of water) and seal. Ready in seven days. When the supplier of this recipe was told his recipe did not keep too long he replied: "If you like pickled olives there will be no need for them to keep!"

Favourite Greek Pickling Method Back to top

There are many different ways to prepare olives and the following old Greek recipe is one of the simplest. Commercial pickling processes generally use caustic soda, food acids and salt. This old fashioned recipe uses salt only.

Olives can be pickled when green or black. A black olive is simply a ripe olive. Generally the green olives are used for pickling. Some black olives are pickled and pressed for oil.

In about February - March, some of the fruit begins to turn from plain green to purplish black. When some of the olives begin to change towards black, it will be fairly safe to pick the green olives for pickling.

If the tree is large, place cloth sheets on the ground and strip the fruit from the tree with your hands or with a rake with suitably spaced prongs. Collect the fruit from the sheet, remove odd stems and leaves and rinse olives in clean water in a bucket.

Place the olives on a clean stone surface or cutting board and bruise them with another stone or hammer. Alternatively prick several times with a fork, or make three slits in the skin of each olive with a small serrated knife while turning the fruit between the thumb and index finger. This bruising, pricking or cutting will allow the water and salt to penetrate the fruit thereby drawing out the bitterness and also preserving it. This will also do away with the need to use a caustic soda solution as used in commercial processing of olives.

Toss them immediately into a bucket of clean water in which one half cup of coarse or cooking salt has been dissolved into every ten cups of water. A clean plate can be placed on top to keep the olives submerged. All olives must be under the liquid. Pour the liquid away each day and replace with fresh salt water. Repeat this washing process for about 12 days for green olives and about 10 days for black (ripe) olives. The best test is to bite an olive. When the bitterness has nearly gone, the olives are ready for the final salting. As you can see, this simple recipe involves the disposal of salty rinse water into the environment. If you decide to commercially pickle olives, there are other recipes that require a longer pickling time but do not result in salty waste water.

Pour off and measure the last lot of water so you will know the volume of salt brine that will be required. Measure that quantity of fresh, warm water into a pan and dissolve the salt, this time at the rate of 1 cup of salt to 10 cups of water. Bring the salt water preserving mixture to the boil and allow tocool. Place olives in bottles and then pour the salt water brine over them until the fruit is completely submerged. Top up the bottles with up to one centimetre of olive oil to stop air getting to the fruit and seal the lids on. No further preparation is required and the bottled olives will store for at least 12 months in a cool cupboard.

When you are ready eat your olives, pour out the strong preserving solution and fill the jar with clean, cool water. Leave in the refrigerator for 24 hours and taste them. If they are still too salty for your liking, then refill the bottle with a fresh lot of water and return to the refrigerator for a further 24 hours. (The plain water leaches some of the salt back out of the olives). At this stage you can also add any or all of the following flavourings: Grated garlic, basil, oregano, chopped onion, red capsicum, lemon juice and lemon pieces. Especially popular is a combination of garlic, basil and lemon juice.

Now sit back and enjoy the unique flavour of your own olives. You will probably never want to buy chemicalized commercial olives again.

WARNING!

Don't give any of your olives to your olive eating friends to taste or you might finish up with more friends than olives! Tell them to buy themselves a tree - or better still, set up a whole olive grove.

Pickling Peasant Style by Lynne Chatterton, Umbria - Italy

(Extracted from Australian Olive Grower, Issue 5, January 1998) Back to top

"I was interested in the section on pickled olives in the last issue. I've been playing around for some years with different ways of preserving olives and have discovered some very simple methods that may be of interest to your readers.

In Umbria we have a range of uses for olives besides the oil of which we are justly proud. We use them when cooking dishes 'al cacciatore' - the method used by hunters (for instance with wild boar, pigeons, rabbit and pork) - we use them in bread and in pizzas, and we eat them on their own.

Olives to be used in various types of casseroles and stews don't require much work. I have a friend who cooks in one of our best restaurants here. The restaurant is famous for its pigeon dishes which have olives as part of the recipe. He simply takes small black olives directly from the tree and freezes small quantities in plastic bags and then puts them directly into the casserole when cooking begins. I've tried this and it works very well.

My neighbour (a woman of 80 years), takes fresh black olives and packs them into one litre lidded jars with rock salt and leaves them for a couple of months, then rinses them off and uses them straight away in cooked dishes and also for eating with prosciutto or salad. This is another simple yet effective preparation.

I have a Tunisian friend who is a mine of information about traditional products there and he showed me how to preserve olives Tunisian peasant style. You need a shallow tray with sides, two pieces of strong reasonably fine wire netting and several heavy stones. The olives are spread out on the netting (or plastic open weave shelf) which is suspended over a shallow tray. The fruit is interspersed with coarse rock salt and branches of fresh rosemary. The top piece of netting is put on and the whole package is weighted down with heavy stones. The olives are put outside (sheltered from rain) and left for about three weeks. At the end of this time juice from the olive should have leached out into the tray. If not, leave them until it has. Rinse the olives, pack them in jars, cover with either a salt solution or with olive oil. Add some rosemary twigs, black pepper, orange and lemon peel, a clove of garlic and put on the lid and leave until they are needed. I used 2 pieces of rigid netting 30 x 20 cm and it worked very well.

I picked up a tip from Maggie Beer's Book (Maggie's Orchard) that is quite useful. Like most cooks I am always left with part jars of olives I've used for bread or pizza, or half dishes of olives I've put out for nibbles. What to do with them? I keep a glazed terracotta lidded container in the kitchen and put all these olives in there with oil, a dash of wine vinegar, and some weak saline. As long as the olives stay under this mixture they keep very well and when I want to use some, I use a small sieve to get them out and add herbs or spices as I want. By the way, crushed Coriander seeds go very well with olives.

This year I'm using the Greek and Italian method I've used in the past for initial preserving. I picked some large green olives, and the usual medium sized black olives. I do between 2 to 3 kgs of each. With both lots I used a sharp knife to cut across on one side. I then put them into fresh water in a large bowl so that the water is well above them and also between them. I left the green olives for a couple of weeks and the black olives a week or so longer. I changed the water every two days.

Towards the end of the fortnight I began to add a bit of rock salt because, although I've never had olives go off in this process, we had a bit of warm weather and I was being prudent. At the end of this process I put the green olives into a strong solution of brine - about 1 cup of coarse rock salt to 8 cups of water - in a 3kg Kilner jar, and put a half inch of olive oil on top before sealing. These are now in my cool, dark pantry and will stay there for about six months before I begin to use them.

The black olives (which took longer to lose their harsh bitterness), have been rinsed and packed into the jar with the same saline solution as above plus 150mls of malt vinegar (I couldn't get this here so have used some white wine vinegar), and some rosemary, some black peppercorns, and topped the lot with half an inch of olive oil before sealing and storing in the pantry.

Another neighbour here tells me that she never adds aromatics to her olives until the night before she wants to eat as antipasto. Then she takes them from the storage jars in which they live and puts them in a solution of oil, weak saline and a little vinegar, and adds lemon and orange peel, rosemary, garlic, chilli, coriander seed, black pepper, alone or in combination, and soaks them overnight. She takes them out about and hour before using them and serves them in small dishes. I can guarantee they are delicious.

Olives here are also just dried outside in the fresh air and then salted and stored in jars without any liquid or oil at all. They are taken out and rinsed and used just as they are. The same thing is done with tomatoes. Strings of tomatoes hang from every contadino household at the end of summer. Onions and garlic are also dried outdoors and keep very well because of it.

In my experience, the critical thing is to leave the olives in their brine or brine mix for as long as possible before using them. Whatever method you use to process your olives, the flavour needs about six months to become acceptable for eating. I've known people forget they have stored olives in dark places in a saline solution for a couple of years and then found to their surprise that they are delicious. Salt seemed to be a common means of leaching out the bitterness but once that is done a combination or salt, vinegar, and oil (all traditional preservatives) can be mixed or used alone to preserve the fruit. Alternatively, drying alone is a perfectly acceptable way of preserving olives.

One has to remember that olive preservation has been a tradition in peasant societies where complicated methods, fancy utensils and sophisticated chemicals are not possible or available. Today, wooden tubs, and terracotta storage pots are chic and not easily obtainable in anglo-saxon countries (although I can get them easily and cheaply here), but a large crockery bowl and glass preserving jars are, salt and vinegar are cheap and handy, and oil is always available, so one can simply adapt the peasant methods to one's kitchen.

We don't grow large quantities of table olives here in Umbria so all our recipes are for olives we take from our existing trees - Frantoio, Leccino, Dolce Agogia, Moraiolo, and, in our case, some very old and unnamed varieties that we inherited. We have planted some Spanish and Greek table varieties but to date they've had little fruit as we suffered from severe frosts and hail for their first two years of growth. I've found our oil olives quite good for both eating and cooking. - Lynne Chatterton - Umbria, Italy."

Ash and Olives! by Craig Hill Back to top

Craig Hill has very kindly sent us this 'environmentally friendly' pickling recipe.

Following last issue's pickling recipe article, you might be interested in the following green table olive recipe adapted from "L'Olivier et la préparation des olives en Provence: recettes familiales" by Max Lambert:

1. Crush and sift a quantity of new wood ash; the weight of the ash should be equal to the weight of the olives to be prepared. The olives should be freshly picked, clean and undamaged.

2. Make a fairly liquid paste by pouring boiling water on the ash. Cover and allow to cool completely.

3. Carefully stir in the olives to coat them with the ash paste.

4. Gently stir the olives once daily for 5 to 7 days.

5. Towards the end of the week, cut several olives lengthwise; the 'désamérisation' ["de-bitter-isation"] is complete when the fruit has darkened to about 1mm from the stone.

6. Rinse the olives clean [dispose of the ash paste and contaminated water thoughtfully] and submerge them in clean water (avoiding contact with the air); the water should be changed every 4 or so hours for the first day, then daily for 3 or 4 more days. This process is finished when the water remains clear and has no or little rusty discoloration. [At this stage you should also taste the fruit: although the flavour will be rather crude, the bitterness should have all but disappeared.]

7. Preserve in sterile jar(s) in a saline solution or vinegar mixture as in the usual recipes, adding aromatic herbs, garlic, lemon pieces to taste and with a 5mm layer of olive oil.

The concentration of the preservative/saline solution in point 7 should be sufficient to partially float an egg or a small potato. Personally I err on the generous side with the salt (thinking that the olives are doing me so much good that the body can probably tolerate a bit more salt!). Depending on the aromatics, I've usually added about 10% vinegar. An Italian contact also taught me the trick of keeping the olives submerged by placing a 'wreath' of wild fennel stalks under the lid.

An unusual method but with a sound explanation! Wood ash is about as alkaline as the usual soda/lye recipes and this neutralises the oleopicrine. The advantage of this "alkaline" bath is that, done properly, it preserves the integrity ie the flavour, firmness and colour of the fruit. The advantage of this method is that it 'appears' to be a bit more environmentally friendly than using caustic or washing soda. There is still the problem of disposing of the strongly alkaline paste, but it seems to be less environmentally disastrous than some other methods. - Craig Hill"

INFORMATION SHEET

What is a DOP Closure and how do you apply it to an Olive Oil glass bottle? Once the olive oil has been filled into the bottle you can see the video on how to apply.

This video shows how a DOP closure can be applied to the olive oil bottle. The non-refillable DOP snap closure once fitted is not removable. The DOP is considered safe, hygienic and very easy to apply even without the need for machinery. One pressure application can have the DOP applied to the bottle and is ready to remove the tamper-evident seal and pour the olive oil directly from the bottle.

The non-refillable system is a new type that can be seen across Europe without the need for applying the thread to the bottle.

This season's olive oil production is expected to total 1.5 million tons.Photographer: Angel Garcia/Bloomberg

October 2023: According to recent forecasts from the European Commission, European households should brace for another year of soaring olive oil prices. Despite hopes for relief, the surge shows no signs of slowing as climatic pressures and limited reserves continue to strain supply across key producing regions.

The new season, which began this month, is projected to bring a total output of around 1.5 million tons. That figure represents just a 9% increase compared to last year—far from enough to restore balance in the market. Ongoing drought conditions have once again weighed heavily on growers, leaving orchards in regions like Jaén, Spain, with reduced yields. With stocks already low, prices in these major hubs have escalated dramatically, nearly tripling the five-year average.

These record highs have filtered down into everyday life, keeping the cost of Mediterranean staples such as pizza and paella uncomfortably high, even as inflation begins to cool in other sectors. Consumers across the European Union are expected to cut back, with the Commission predicting a 6% drop in olive oil consumption during the 2023–24 season. Exports are also forecast to decline by about 10% compared to the previous year.

The rally has already pushed olive oil to unprecedented price levels this year, and according to Brussels, the market’s upward momentum will likely persist for another 12 months. For growers and industry stakeholders, the news underscores how tightly climate extremes and limited inventories are reshaping supply and demand in one of Europe’s most cherished food sectors.

Reference

Sydney, Australia — October 20: In recent days, Sydney welcomed a delegation from the International Olive Council, comprising Maria Juarez, Head of Promotion and Economic Affairs; Dr. Imene Trabelsi Trigui, Head of Promotion; and Dr. Wenceslao Moreda, Principal Scientist and IOC specialist.

Their visit was intended to deliver a program of events in Sydney, including a two-day technical tasting workshop and a formal networking cocktail reception.

The objectives of these events were twofold. The workshop sought to strengthen collaboration between Australian growers, producers, and the International Olive Council, while the networking cocktail reception united key stakeholders — including government officials, media representatives, chefs, and producers — in a dynamic exchange. A highlight of the evening was the introduction of the newly appointed Ambassador, Mark Olive, who captivated guests with a specially crafted menu featuring Australian Indigenous ingredients such as saltbush, kangaroo, bush tomato, and native peppers, elegantly paired with a selection of Australian Extra Virgin Olive Oils.

“Advancing sustainability in olive oil production is essential to tackling climate change. We encourage producers to embrace sustainable methods that not only reduce environmental impact but also help optimize production costs. Australia’s strengthened partnership with the IOC represents a step toward a healthier and more sustainable future. Our mission is to promote greater awareness of olive oil’s benefits and sustainable practices, fostering improved and healthier consumption.” — Dr. Imene Trabelsi, Head of Promotions, International Olive Council

The two-day technical workshop was led by Dr. Wenceslao Moreda, an IOC specialist and Chair of the eWG of the Codex Committee on Fats and Oils (CCFO). A distinguished member of the Spanish National Research Council, Dr. Moreda holds an impressive record of over 75 research publications dating back to 1995. The opening day of the workshop focused on sensory evaluation, addressing both the physical and psychological dimensions of the organoleptic process while emphasizing the importance of proper production conditions in compliance with the rigorous standards established by the International Olive Council. The discussions provided valuable insight into the rationale behind these standards and the allowances for specific variances, reinforcing their role as the overarching global benchmark.

On the second day, the workshop focused on the quality and purity of Extra Virgin Olive Oil, examining internal quality control measures and evaluation criteria. The program concluded with an in-depth review of health-related parameters associated with olive oil, attended by nutrition experts. The breadth of technical knowledge shared proved highly valuable, offering participants a holistic understanding of the journey from production to final product from an organoleptic perspective. During the session, the IOC also announced the development of a new website dedicated to communicating the extensive health benefits of olive oil.

The International Olive Council continues to be a steadfast leader in shaping the global olive oil sector, establishing standards and fostering international collaboration essential to the industry’s advancement. As these remarkable events draw to a close, they leave a lasting impression of unity, progress, and shared commitment to the treasured ‘liquid gold’—extra virgin olive oil.

Beyond celebrating the richness and versatility of olive products, these gatherings underscored the critical importance of cooperation and knowledge exchange within the global olive community.

The International Olive Council (IOC) functions as the leading intergovernmental organization responsible for establishing the regulatory framework governing the global olive oil sector. Although Australia is not yet an official IOC member, it actively supports the organization by assisting emerging industries in adopting and applying international standards. The cooperation demonstrated during recent events underscored the IOC’s global significance and lasting impact.

The IOC also recognizes the diversity of growing conditions worldwide, which may lead to parameter variations outside of established guidelines in certain producing regions. Importantly, the IOC administers the only legally binding international standard for olive oil, reinforcing its critical role from a legislative and regulatory perspective. Complementing this, the Australian Olive Oil Association (AOOA) is acknowledged for its collaborative work with the IOC, further highlighting the importance of sustained international cooperation within the sector.

IOC Membership Process

The International Olive Council maintains strict criteria for membership. Participation is reserved exclusively for governments or international organizations empowered to negotiate, conclude, and implement international agreements, particularly those relating to commodities.

When a country seeks to join the IOC, its government must formally apply to the Council of Members, typically through its Ministry of Foreign Affairs, another relevant ministry, or its Embassy in Spain. The Council then reviews the application, establishes terms and conditions of accession — including financial contributions to the IOC budget — and sets a deadline for depositing the instrument of accession with the Secretary-General of the United Nations in New York, who serves as the official depository of the Agreement.

Upon successful deposition, the applicant nation becomes a full IOC Member. Private companies and individuals are not eligible for membership. Additionally, all European Union Member States are automatically represented in the IOC through the EU’s membership, without the need for separate applications.

In Australia’s case, stronger collaboration between national associations, government agencies, and the IOC will be essential for achieving closer alignment with international standards. Leadership from within the Australian olive oil industry itself will be critical in driving forward discussions on potential membership.

IOC Health Website

The IOC has recently launched a new website serving as a comprehensive reference hub on olive oil and health.

IOC Standards, Methods, and Guidelines

The IOC continues to provide the latest updates on trade standards for olive oil and table olives, as well as official testing protocols, sensory (organoleptic) assessment methods, and quality management practices.

INDUSTRY NEWS

The NSW Department of Primary Industries’ (DPI) Wagga Wagga Edible Oils Laboratory - a cornerstone of Australia’s olive and oilseed testing infrastructure - is expected to cease operations by Christmas 2025, with sample submissions accepted only until mid-November. The closure represents a significant loss for growers, processors, and exporters who have relied on the lab’s internationally accredited testing services for more than two decades.

Located within the Wagga Wagga Agricultural Institute, the DPI’s edible oils laboratory has been one of Australia’s few facilities accredited to NATA, AOCS, and International Olive Council (IOC) standards. It has played a critical role in verifying olive oil quality, authenticity, and export compliance, as well as providing trusted testing for canola and other oilseeds.

The lab’s closure follows the NSW Government’s announcement of widespread job cuts across the Department of Primary Industries - around 165 positions statewide - raising alarm among regional industries dependent on these essential technical services.

According to industry updates, the Wagga team will continue accepting samples until approximately 14 November 2025, before winding down operations ahead of Christmas. After that point, testing services will no longer be available through the Oil Testing DPI Laboratory.

While the department has yet to make a detailed public statement about the transition plan, producers are being advised to prepare for changes now, especially those requiring export certification or routine oil-quality analyses.

The loss of this facility is being described as a major setback for the Australian olive industry, particularly for small to mid-sized growers in New South Wales and surrounding regions. The Wagga lab’s proximity and affordability have long made it a practical option for quality assurance, benchmarking, and product validation - key factors in maintaining consumer trust and market competitiveness.

Its closure could mean:

With the Wagga Wagga laboratory closing, industry attention is turning toward Modern Olives Laboratory Services in Victoria, which offers a full suite of IOC-listed testing options, though it is not currently IOC-accredited for olive oil and related products in 2025. Modern Olives Laboratory holds AOCS recognition for both chemical and sensory analysis for 2025, as well as a TGA licence covering chemical and physical testing of olive oil derivatives and microbiological testing of olive derivatives only.

Modern Olives is a long-established recognised testing facility providing analytical services to growers, processors, and exporters across Australia and overseas. More information about their services can be found at:

Industry leaders are urging state and federal governments to engage with the olive and edible oil sectors to ensure a smooth transition of testing capabilities and protect the integrity of olive oil standards. Without a coordinated plan, the risk grows that smaller producers could lose access to affordable, timely, and accredited testing - jeopardising both domestic labeling compliance and export eligibility.

As Australia continues to strengthen its reputation for high-quality, traceable olive oil, maintaining a strong laboratory infrastructure is essential. The Wagga Wagga lab’s closure marks the end of a chapter in regional agricultural science, but it also highlights the need for ongoing investment in independent, nationally recognised testing to support the industry’s future growth.

For further information:

MARKET INSIGHT: GLOBAL OLIVE OIL ECONOMY 2023

Introduction

The global olive oil industry in 2023 has entered uncharted territory, experiencing an extraordinary surge in olive oil prices driven by a combination of climatic and economic forces. At the centre of this crisis lies Spain’s devastating drought, which has crippled the world’s largest olive oil producer. This severe shortage has led to a dramatic contraction in olive oil supply, triggering price escalation and a corresponding decline in consumer demand. The ripple effects are being felt worldwide, reshaping the balance between producers and consumers alike. Meanwhile, Australian olive oil producers find themselves in a rare position of advantage, benefitting from unprecedented market highs. This article explores the causes, consequences, historical trends, and economic signals surrounding this remarkable global olive oil price spike.

The ongoing drought across Spain stands as the principal factor behind the current olive oil price surge. As one of the largest olive oil-producing nations globally, Spain’s drastically reduced harvest - caused by months of extreme heat and minimal rainfall - has sharply curtailed olive oil availability in both European and international markets. This has intensified supply shortages, compelling consumers to pay more for what has long been a staple Mediterranean product. The interplay of limited supply and escalating demand has magnified price volatility, reinforcing the classic supply-and-demand imbalance now driving global markets.

Incredible to see the olive groves of Jaen, Spain. This one province produces around a fifth of the *entire* global supply of olive oil

— Secunder Kermani (@SecKermani) August 31, 2023

But a combination of drought & extreme heat has left many trees badly weakened... This years harvest looks set to be the worst in living memory pic.twitter.com/QYs41eXCwC

As prices have risen steeply, the shortage of olive oil has led to a noticeable decline in consumption, particularly in Spain, where demand has reportedly dropped by around 35%. Consumers are now scaling back their purchases, finding olive oil increasingly unaffordable compared to other cooking oils. The once-steady household consumption patterns are shifting as people seek alternatives or modify their cooking habits. This contraction in domestic demand not only highlights the growing accessibility gap for consumers but also underscores the broader economic strain caused by high inflation and food price increases.

Amid the turmoil, Australian olive oil producers are experiencing a windfall. Thanks to limited global supply, Australian growers are commanding record prices exceeding AUD $8 per litre, marking the highest levels ever recorded in the nation’s olive oil industry. This lucrative period presents a rare opportunity for Australian exporters, with demand from Europe - including Spain itself - now turning toward Australian supplies. For producers Down Under, this unique reversal of roles underscores how regional climate resilience and diversified production can translate into significant financial gains when global shortages arise.

The olive oil market’s volatility is not a new phenomenon. Previous spikes occurred in 1996, 2006, and 2015, each triggered by weather-related supply constraints. Yet, the 2023 price explosion stands out as the most dramatic in recorded history -over 40% higher than any previous price peak, and roughly double the magnitude of earlier surges. This extreme escalation reflects not just climatic hardship but a clear pricing bubble forming within the market, echoing the cyclical nature of commodity pricing.

The olive oil sector has long followed cyclical pricing patterns, typically alternating between low and high price phases roughly every decade. The current surge aligns almost perfectly with the predicted start of another 10-year cycle, occurring just three years into its anticipated timeline. Furthermore, a notable correlation has been identified between the Australian Food Inflation Index and the Global Olive Oil Price Index as reported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This connection illustrates the deep interdependence between food commodity pricing and global economic conditions.

While the IMF’s benchmark prices are denominated in USD, for the purposes of this analysis they have been converted to AUD to track the trend relative to Australian markets. These benchmark indicators -based on the world’s largest olive oil exporters -serve as a reliable gauge of overall market direction, confirming how global shortages and inflationary pressures move in tandem.

Global olive oil prices show a recurring 10-year cycle, driven by droughts, crop shortages, and rising production costs

Global olive oil prices show a recurring 10-year cycle, driven by droughts, crop shortages, and rising production costs

From a technical analysis perspective, the Relative Strength Indicator (RSI) is often used to measure price momentum and potential overextension in markets. On recent olive oil price charts, the RSI (represented in purple) indicates that prices have once again entered overbought territory - a level seen during previous speculative phases. Historically, such readings have preceded market corrections or reversals, suggesting that the current surge may not be sustainable in the long term.

Analysts caution that as the European olive harvest begins in September and October 2023, an influx of new oil supplies could help ease prices, though the timing and extent of this correction remain uncertain. Until then, speculative trading and limited inventory continue to support inflated market values.

The record-breaking olive oil prices of 2023, primarily triggered by Spain’s drought-induced production collapse, mark a turning point for the global olive oil economy. With consumer demand declining under the pressure of soaring prices and Australian producers thriving amid the scarcity, the industry is experiencing a dramatic rebalancing. Historical precedents, cyclical trends, and market indicators all point toward a complex, transitional period defined by volatility and uncertainty.

As the world’s producers, traders, and consumers adapt to these new market dynamics, one truth remains clear: olive oil - celebrated for its taste, health benefits, and cultural significance - continues to be at the mercy of both climate change and economic cycles. Stakeholders across the value chain must remain alert, flexible, and forward-thinking as the olive oil market navigates this extraordinary phase of transformation.

Other Sources

This season's olive oil production is expected to total 1.5 million tons.Photographer: Angel Garcia/Bloomberg

October 2023: According to recent forecasts from the European Commission, European households should brace for another year of soaring olive oil prices. Despite hopes for relief, the surge shows no signs of slowing as climatic pressures and limited reserves continue to strain supply across key producing regions.

The new season, which began this month, is projected to bring a total output of around 1.5 million tons. That figure represents just a 9% increase compared to last year—far from enough to restore balance in the market. Ongoing drought conditions have once again weighed heavily on growers, leaving orchards in regions like Jaén, Spain, with reduced yields. With stocks already low, prices in these major hubs have escalated dramatically, nearly tripling the five-year average.

These record highs have filtered down into everyday life, keeping the cost of Mediterranean staples such as pizza and paella uncomfortably high, even as inflation begins to cool in other sectors. Consumers across the European Union are expected to cut back, with the Commission predicting a 6% drop in olive oil consumption during the 2023–24 season. Exports are also forecast to decline by about 10% compared to the previous year.

The rally has already pushed olive oil to unprecedented price levels this year, and according to Brussels, the market’s upward momentum will likely persist for another 12 months. For growers and industry stakeholders, the news underscores how tightly climate extremes and limited inventories are reshaping supply and demand in one of Europe’s most cherished food sectors.

Reference

Sydney, Australia — October 20: In recent days, Sydney welcomed a delegation from the International Olive Council, comprising Maria Juarez, Head of Promotion and Economic Affairs; Dr. Imene Trabelsi Trigui, Head of Promotion; and Dr. Wenceslao Moreda, Principal Scientist and IOC specialist.

Their visit was intended to deliver a program of events in Sydney, including a two-day technical tasting workshop and a formal networking cocktail reception.

The objectives of these events were twofold. The workshop sought to strengthen collaboration between Australian growers, producers, and the International Olive Council, while the networking cocktail reception united key stakeholders — including government officials, media representatives, chefs, and producers — in a dynamic exchange. A highlight of the evening was the introduction of the newly appointed Ambassador, Mark Olive, who captivated guests with a specially crafted menu featuring Australian Indigenous ingredients such as saltbush, kangaroo, bush tomato, and native peppers, elegantly paired with a selection of Australian Extra Virgin Olive Oils.

“Advancing sustainability in olive oil production is essential to tackling climate change. We encourage producers to embrace sustainable methods that not only reduce environmental impact but also help optimize production costs. Australia’s strengthened partnership with the IOC represents a step toward a healthier and more sustainable future. Our mission is to promote greater awareness of olive oil’s benefits and sustainable practices, fostering improved and healthier consumption.” — Dr. Imene Trabelsi, Head of Promotions, International Olive Council

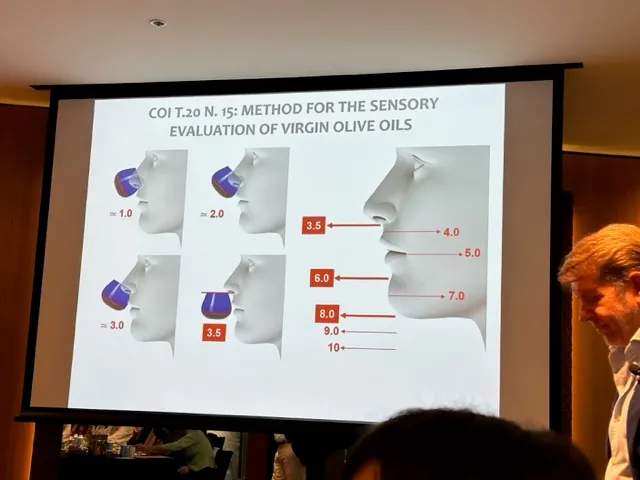

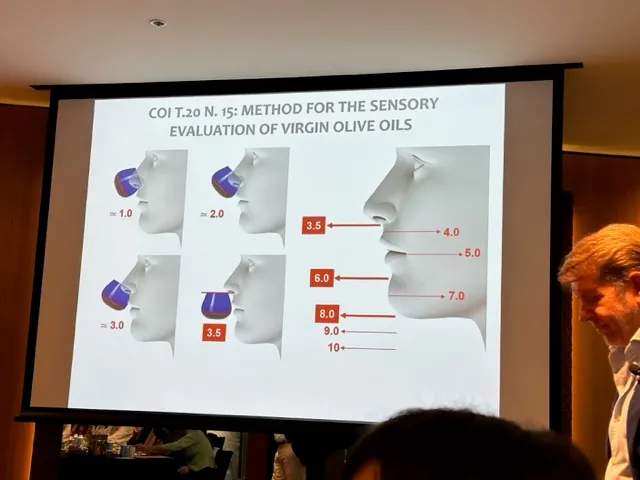

The two-day technical workshop was led by Dr. Wenceslao Moreda, an IOC specialist and Chair of the eWG of the Codex Committee on Fats and Oils (CCFO). A distinguished member of the Spanish National Research Council, Dr. Moreda holds an impressive record of over 75 research publications dating back to 1995. The opening day of the workshop focused on sensory evaluation, addressing both the physical and psychological dimensions of the organoleptic process while emphasizing the importance of proper production conditions in compliance with the rigorous standards established by the International Olive Council. The discussions provided valuable insight into the rationale behind these standards and the allowances for specific variances, reinforcing their role as the overarching global benchmark.

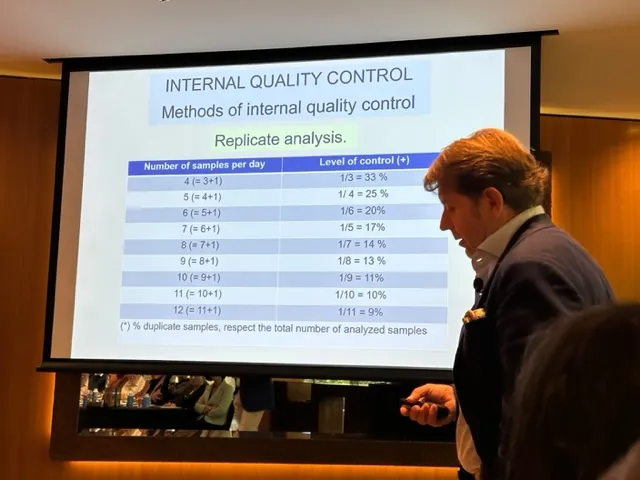

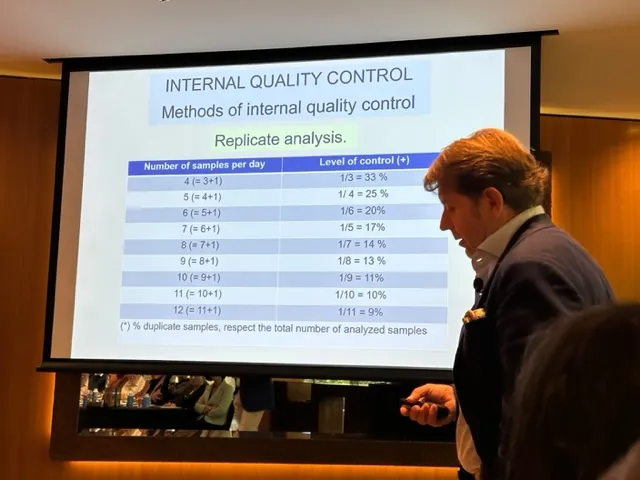

On the second day, the workshop focused on the quality and purity of Extra Virgin Olive Oil, examining internal quality control measures and evaluation criteria. The program concluded with an in-depth review of health-related parameters associated with olive oil, attended by nutrition experts. The breadth of technical knowledge shared proved highly valuable, offering participants a holistic understanding of the journey from production to final product from an organoleptic perspective. During the session, the IOC also announced the development of a new website dedicated to communicating the extensive health benefits of olive oil.

The International Olive Council continues to be a steadfast leader in shaping the global olive oil sector, establishing standards and fostering international collaboration essential to the industry’s advancement. As these remarkable events draw to a close, they leave a lasting impression of unity, progress, and shared commitment to the treasured ‘liquid gold’—extra virgin olive oil.

Beyond celebrating the richness and versatility of olive products, these gatherings underscored the critical importance of cooperation and knowledge exchange within the global olive community.

The International Olive Council (IOC) functions as the leading intergovernmental organization responsible for establishing the regulatory framework governing the global olive oil sector. Although Australia is not yet an official IOC member, it actively supports the organization by assisting emerging industries in adopting and applying international standards. The cooperation demonstrated during recent events underscored the IOC’s global significance and lasting impact.

The IOC also recognizes the diversity of growing conditions worldwide, which may lead to parameter variations outside of established guidelines in certain producing regions. Importantly, the IOC administers the only legally binding international standard for olive oil, reinforcing its critical role from a legislative and regulatory perspective. Complementing this, the Australian Olive Oil Association (AOOA) is acknowledged for its collaborative work with the IOC, further highlighting the importance of sustained international cooperation within the sector.

IOC Membership Process

The International Olive Council maintains strict criteria for membership. Participation is reserved exclusively for governments or international organizations empowered to negotiate, conclude, and implement international agreements, particularly those relating to commodities.

When a country seeks to join the IOC, its government must formally apply to the Council of Members, typically through its Ministry of Foreign Affairs, another relevant ministry, or its Embassy in Spain. The Council then reviews the application, establishes terms and conditions of accession — including financial contributions to the IOC budget — and sets a deadline for depositing the instrument of accession with the Secretary-General of the United Nations in New York, who serves as the official depository of the Agreement.

Upon successful deposition, the applicant nation becomes a full IOC Member. Private companies and individuals are not eligible for membership. Additionally, all European Union Member States are automatically represented in the IOC through the EU’s membership, without the need for separate applications.

In Australia’s case, stronger collaboration between national associations, government agencies, and the IOC will be essential for achieving closer alignment with international standards. Leadership from within the Australian olive oil industry itself will be critical in driving forward discussions on potential membership.

IOC Health Website

The IOC has recently launched a new website serving as a comprehensive reference hub on olive oil and health.

IOC Standards, Methods, and Guidelines

The IOC continues to provide the latest updates on trade standards for olive oil and table olives, as well as official testing protocols, sensory (organoleptic) assessment methods, and quality management practices.

INDUSTRY NEWS

The NSW Department of Primary Industries’ (DPI) Wagga Wagga Edible Oils Laboratory - a cornerstone of Australia’s olive and oilseed testing infrastructure - is expected to cease operations by Christmas 2025, with sample submissions accepted only until mid-November. The closure represents a significant loss for growers, processors, and exporters who have relied on the lab’s internationally accredited testing services for more than two decades.

Located within the Wagga Wagga Agricultural Institute, the DPI’s edible oils laboratory has been one of Australia’s few facilities accredited to NATA, AOCS, and International Olive Council (IOC) standards. It has played a critical role in verifying olive oil quality, authenticity, and export compliance, as well as providing trusted testing for canola and other oilseeds.

The lab’s closure follows the NSW Government’s announcement of widespread job cuts across the Department of Primary Industries - around 165 positions statewide - raising alarm among regional industries dependent on these essential technical services.

According to industry updates, the Wagga team will continue accepting samples until approximately 14 November 2025, before winding down operations ahead of Christmas. After that point, testing services will no longer be available through the Oil Testing DPI Laboratory.

While the department has yet to make a detailed public statement about the transition plan, producers are being advised to prepare for changes now, especially those requiring export certification or routine oil-quality analyses.

The loss of this facility is being described as a major setback for the Australian olive industry, particularly for small to mid-sized growers in New South Wales and surrounding regions. The Wagga lab’s proximity and affordability have long made it a practical option for quality assurance, benchmarking, and product validation - key factors in maintaining consumer trust and market competitiveness.

Its closure could mean:

With the Wagga Wagga laboratory closing, industry attention is turning toward Modern Olives Laboratory Services in Victoria, which offers a full suite of IOC-listed testing options, though it is not currently IOC-accredited for olive oil and related products in 2025. Modern Olives Laboratory holds AOCS recognition for both chemical and sensory analysis for 2025, as well as a TGA licence covering chemical and physical testing of olive oil derivatives and microbiological testing of olive derivatives only.

Modern Olives is a long-established recognised testing facility providing analytical services to growers, processors, and exporters across Australia and overseas. More information about their services can be found at:

Industry leaders are urging state and federal governments to engage with the olive and edible oil sectors to ensure a smooth transition of testing capabilities and protect the integrity of olive oil standards. Without a coordinated plan, the risk grows that smaller producers could lose access to affordable, timely, and accredited testing - jeopardising both domestic labeling compliance and export eligibility.

As Australia continues to strengthen its reputation for high-quality, traceable olive oil, maintaining a strong laboratory infrastructure is essential. The Wagga Wagga lab’s closure marks the end of a chapter in regional agricultural science, but it also highlights the need for ongoing investment in independent, nationally recognised testing to support the industry’s future growth.

For further information: