My Shopping Cart

My Shopping Cart

| File | Title | File Description | Type | Section |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultivar_Brochure.pdf | Oliomio Cultivar Olive Oil Processing Brochure by Toscana Enologica Mori | Brochures | Document |

OLIVE OIL PROCESSING

For businesses and serious growers considering olive oil extraction, the idea of owning a machine for under $10,000 may seem like an attractive entry point. However, achieving high-quality olive oil requires advanced extraction technology that meets food-grade standards. The extraction process is highly technical, demanding specialised equipment to maintain oil integrity and efficiency. This guide will help you understand the essential components of olive oil processing, the investment required, and the best options for entering the market.

Many low-cost machines marketed for oil extraction—often priced around $2,000—are screw presses designed for seed and nut oils. These do not meet the requirements for proper olive oil extraction. Producing premium extra virgin olive oil requires specialised machinery that includes:

Without these advanced components, it is impossible to produce high-quality olive oil that meets commercial standards.

Each of these stages demands industrial-grade technology, making low-cost extraction machines impractical for producing high-quality olive oil.

For those serious about maintaining full control over their production, the Frantoino Olive Oil Press is an excellent entry-level option. With a processing capacity of up to 50kg per hour, it delivers professional-quality results in a compact and efficient design. Owning your own machine ensures complete flexibility and control over your olive oil production.

f you’re looking for a cost-effective alternative, buying a used machine can provide savings while still allowing you to own your equipment. Though used machines can be harder to source, platforms such as Olive Machinery list available second-hand units.

For those not ready to invest in machinery, a local processing facility provides access to high-grade extraction equipment without the capital investment. To find a processor near you, use The Olive Centre’s Processor Map.

Producing high-quality olive oil requires investment in the right equipment and processes. Whether you choose to own a professional machine like the Frantoino, explore second-hand options, or utilise a local processing service, there are solutions to suit different business needs. For those prioritising full control and flexibility, investing in specialized extraction equipment is the best path forward. However, used equipment and local processors provide accessible alternatives for those looking to test the market before committing to a larger investment.

OLIVE OIL PROCESSING SOLUTIONS

If you are looking for small-scale olive oil processing machines, olive oil processing machine prices, compact olive oil processing equipment for boutique groves, olive oil extraction machines for home use, olive oil press machines in Australia, the best home olive oil presses, and affordable olive oil processing machines for sale - many of which are available through The Olive Centre’s renowned range of processing, milling and extraction solutions.

Thinking about pressing your own olive oil for under $10,000 may seem tempting, especially for hobby growers. But when it comes to creating top-tier olive oil, a simple, budget-friendly machine won’t meet the needs. Producing quality oil requires carefully managed steps and solid equipment. Here's a clear look at how the process works and how beginners can get started without compromising quality.

Some machines, often sold for a few thousand dollars, claim to produce olive oil. But most of these are screw presses, which are more suited for seeds or nuts - not olives. For real olive oil extraction, you’ll need machinery built specifically to crush, knead, and separate the oil from the paste using centrifugal force. This setup ensures a high yield and preserves the oil’s natural flavour and antioxidants.

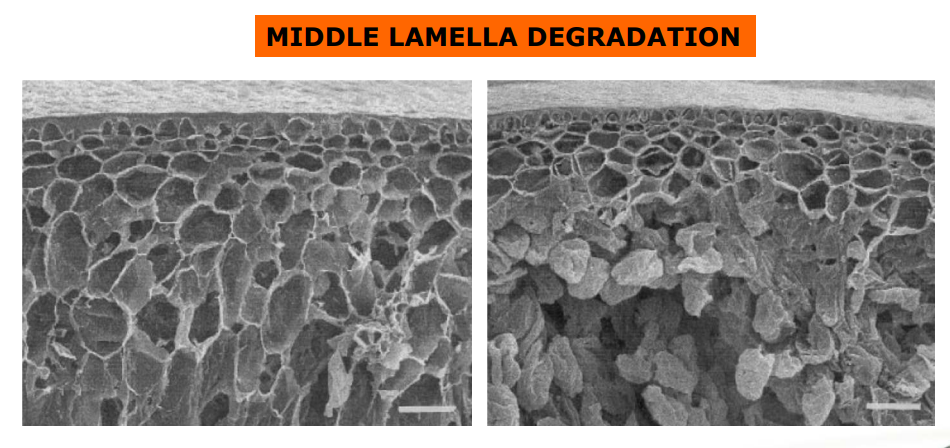

Getting into the actual steps means dealing with tough-skinned olives that need force to break down. From the initial crush to the slow and steady malaxing process, each part of extraction must be carefully controlled. Especially during malaxation, the paste needs to be stirred slowly and kept at the right temperature to let natural enzymes do their job and without this process the cell wall structure of the olive is not broken down to release the oil. This lets the oil separate cleanly during the separation phase of extraction. Machines under $10,000 typically lack the components and processes required to extract olive oil.

Olive oil extraction calls for power, control, and precision. Here's what’s involved:

If you're ready to begin, there are three practical routes depending on your budget and goals:

1. Buy Your Own Press - Frantoino Olive Oil Machine If you want full control and plan to press olives regularly, the Frantoino is a strong entry-level choice. It processes up to 50 kg per hour and gives you hands-on management of every step. You get compact, professional-grade results at home, making this machine perfect for small-scale producers who want flexibility and independence.

2. Consider Pre-Owned Equipment - Not everyone wants to invest in a brand-new setup right away. Buying a used press can cut costs without cutting quality - if you find the right machine. While second-hand units aren't always easy to locate, Olive Machinery has a section for used presses that may suit your needs. This option offers ownership without the higher initial spend.

3. Use a Nearby Processing Service - If you don’t want to buy a machine yet, look into local services that let you use commercial-grade equipment without owning it. This gives you access to professional tools without long-term costs. The Olive Centre’s processor map helps you find a service near you. This option is ideal for first-timers or those with smaller harvests.

Getting into olive oil production takes careful thought, but there are solid options for newcomers. Whether you want full control, a used machine that is cheaper on the budget, or access to a local press (see map-link below), there’s a solution that can work for your setup.

If control and consistency matter most, owning a machine like the Frantoino puts you in charge. If budget matters more, used equipment or shared services let you start small and grow. The key is to understand what each step requires and match that to the method that fits your goals.

Resources

Modern extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) production relies on continuous centrifugal extraction, which has largely replaced traditional presses. In a continuous system, olives are cleaned, crushed into paste, and then malaxed (gently mixed) before a horizontal decanter centrifuge separates oil from water and solids. This process is far more efficient and hygienic than the old press-and-mat method, which is now considered obsolete. Key quality factors include processing fruit quickly to avoid fermentation, maintaining low temperatures during malaxation, and minimising exposure to oxygen. For example, transporting olives in ventilated crates and crushing/milling within 24-48 hours of harvest helps prevent heat buildup and unwanted fermentation that could spoil flavour. Cleaning and de-leafing the fruit before crushing is also critical - removing leaves, dirt, and debris ensures no off-flavours or contaminants make it into the oil. Mordern mills typically incorporate washing and leaf-removal steps for this reason.

Temperature control is paramount during extraction. EVOO is generally produced under “cold-press” conditions, meaning malaxation is kept around ≤27 °C to preserve aromatic compounds and polyphenols. Longer malaxation times or higher temperatures can increase yield but will reduce polyphenol content and flavour freshness. Recent research confirms that malaxation time and temperature must be optimised per cultivar e.g., one study found that extending malaxation from 15 to 90 minutes caused polyphenols to drop by up to 70%. In Australian groves, where harvest season temperatures can be high, processors often monitor paste temperature closely and may use heat exchangers or vacuum conditions to control it. Shorter malaxation (20-40 minutes) at moderate temperatures is commonly employed to balance oil yield with quality retention. Equally important is timing from harvest - olives allowed to sit too long (especially in warm conditions) will start fermenting. Using shallow, well-ventilated bins and milling within a day of picking is recommended to keep olives cool and intact. Big Horn Olive Oil in USA, for instance, emphasises rapid processing: they cold-press olives within 2 hours of harvest to “lock in freshness and antioxidants,” drastically reducing oxidation time in between. Such practices help Australian producers achieve long shelf life (18 - 24 months) and vibrant flavour in their EVOO whereas Cockatoo Grove has a Midnight EVOO where they pick and press in the cool of the night.

Ongoing research in Australia has highlighted how harvest timing and orchard factors influence oil quality. As olives mature on the tree, oil yield rises, but phenolic compounds (antioxidants) tend to drop. In field trials across New South Wales and Victoria, early-harvest olives produced oils with higher polyphenol content and longer shelf stability, whereas late-picked fruit gave more mellow oils with lower antioxidant levels. Free fatty acidity and peroxide (rancidity indicators) remained low until fruit became overripe, but antioxidant-rich components like tocopherols and polyphenols decreased as the fruit matured, leading to reduced oxidative stability in late-season oils. Australian producers must therefore balance quantity vs quality: an early pick yields robust, pungent oils rich in healthful polyphenols, while a later pick yields more volume with milder taste. The table below (adapted from industry data) illustrates this trade-off:

| Harvest Time | Oil Yield (% by weight) | Flavor Profile | Antioxidant Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early (greener fruit) | ~12-16% (lower) | Green, grassy, intensely fruity; pronounced bitterness & pungency | High (rich in polyphenols) |

| Mid-Season | ~15-18% (moderate) | Balanced fruitiness; moderate pepperiness | Moderate |

| Late (ripe fruit) | ~20-28% (higher) | Mild, buttery, nutty; low bitterness/pungency | Lower (fewer polyphenols) |

Other local research has examined irrigation effects on oil quality. Water-stressed olive trees (common in Australian summers) often produce smaller, more bitter fruit with higher polyphenol content, whereas heavily irrigated trees yield plumper olives with diluted phenolics but higher total oil output. For example, a study found that deficit-irrigated trees had the highest polyphenol levels (and earlier fruit ripening) in dry years, while fully irrigated trees gave greater oil yields at the cost of some phenolic concentration. These findings underscore that post-harvest decisions (when to pick, how to handle fruit before milling/crushing) are just as crucial as the milling technology itself. Cutting-edge extraction equipment can maximise quality potential, but growers must still deliver quality olives to the mill and process them with urgency to produce premium Australian EVOO.

MORI-TEM offers a spectrum of Oliomio mills to suit different scales, from artisanal boutique producers up to small commercial cooperatives. All share the principles above, but with varying throughputs and degrees of automation. Below is an overview of the current Oliomio lineup and its characteristics:

To summarise the small-to-medium Oliomio models discussed above, the table below compares their capacities and key features:

| Oliomio Model | Throughput | Key Features | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spremoliva C30 | 30-40 kg/hour | Batch malaxer (discontinuous); basic mini-press setup; no built-in heating or automation | Hobbyists, micro-batch or lab use (older design) |

| Frantoino Bio | ~50-60 kg/hour | Continuous 2-phase system; single malaxer; simple controls; single-phase power; adjustable decanter nozzles | Boutique farms, artisanal producers, pilot plants |

| Oliomio 80 Plus | ~70-80 kg/hour | Continuous flow; horizontal malaxer with heating & temperature display; inverter speed control; basic CIP wash kit | Small farms (~0.5-1 ton/day harvest); estate olive groves |

| Oliomio Gold | ~90-100 kg/hour | Enhanced automation (auto malaxer & drum washing, variable-speed feed auger)waste pump included; single or 3-phase | Medium farms (~0.8 ton/day); premium boutique mills needing labour-saving features |

| Oliomio Profy 200 | ~150-200 kg/hour | Dual malaxers for semi-continuous processing; heavy-duty crusher; closed/vacuum malaxing; full automation; waste pump | Cooperative regional mills; small commercial processors (~1.5-2 ton/day) |

Table: Comparison of select Oliomio continuous mill models (MORI-TEM). All feature two-phase extraction, stainless steel construction, and integrated crushers and decanters; higher models add more automation and capacity. Note how the traditional press is absent - even the smallest Oliomio brings modern centrifugal extraction to the farm, highlighting the leap in technology from the old press or “monoblocco” mills of past decades.

For producers scaling beyond the monobloc units, MORI-TEM offers modular olive mill installations that handle larger throughputs while prioritising quality. These systems - marketed under names like Sintesi, Forma, Cultivar, and TecnoTEM Oliomio Sintesi Series - break the extraction process into separate machines (e.g., independent crusher, malaxer group(s), decanter, separator) designed to work in harmony. They introduce features like multiple malaxers for higher throughput, vacuum malaxation technology, and advanced control systems. Importantly, they still operate on the continuous two-phase principle and embody the same hygiene and automation ethos as the smaller Oliomio range. Here’s an overview of each series:

It is instructive to contrast the above Oliomio technologies with the outdated systems they have superseded - namely, the classic hydraulic press and early-generation farm mills (older “monoblocchi” units). Traditional olive presses involved grinding olives (often with stone mills) into paste, spreading that paste onto fibre mats, stacking them, and then applying tons of pressure in a press to squeeze out the oil/water mixture. This method, while romantic, had numerous drawbacks: it was labour-intensive and slow, exposed the olive paste to air for prolonged times, and was hard to keep clean. The mats and press equipment could harbour yeasts or moulds and were difficult to sanitise thoroughly. It was not uncommon for olives to begin fermenting in the interim between harvest and pressing - indeed, historical accounts describe farmers bringing sacks of olives to the mill that were “often already fermenting” by the time they were pressed. The result was oil of inconsistent quality and stability. Continuous centrifuge systems like Oliomio eliminated these problems by moving to an enclosed, stainless-steel process where olives are milled almost immediately after picking, drastically cutting the chance for fermentation or oxidation. The greater hygiene and speed of continuous extraction have improved average oil quality and made defects from processing (such as fusty or musty flavours from fermentation) much rarer in modern operations. As a report on introducing Oliomio technology in Australia noted, “centrifugal extraction…replaced older, labour-intensive systems with continuous-flow designs”, offering better hygiene, efficiency, and capacity - effectively rendering the old press method obsolete in quality-oriented production.

Early small-scale continuous mills (from the 1990s-2000s) were a huge step up from presses, but they lacked some refinements of today’s Oliomio models. For example, many older farm mills did not have automated temperature control for malaxation, nor continuous malaxer flow. The very first “Oliomio” monoblock (created by Tuscan innovator Giorgio Mori) was revolutionary for being compact and continuous, but subsequent generations have added further improvements. A comparison of features illustrates this evolution: the older Spremoliva 30 could only malax in batch mode (no simultaneous crushing while decanting) and had no heating system or temperature display on the malaxer. By contrast, an Oliomio 80 or Gold today has fully continuous malaxing with automated temperature control and readout. Earlier mills often used fixed-speed motors and one-size-fits-all settings, whereas new systems employ inverter drives and adjustable nozzles to accommodate different olive conditions (small, watery olives vs. large, fleshy ones, etc.). Another big leap is in automation: tasks like pomace removal and equipment washing, once manual, are now handled by integrated pumps and wash cycles in machines like the Gold and Profy. This not only reduces labour but also ensures more consistent cleanliness batch after batch. In terms of energy and water usage, modern two-phase decanters are also more sustainable - they eliminate the need for large volumes of dilution water required by traditional three-phase decanters (saving water and the energy to heat it) and produce a simpler waste stream (wet pomace) that can be repurposed or composted more easily than press liquor or black water from old systems.

Crucially, oil quality has improved with each technical advance. Traditional pressing often left higher sediment and water in the oil, necessitating longer settling or filtration and risking quicker oxidation. Continuous centrifugation yields cleaner oil immediately, and the lack of air contact preserves freshness. Chemical measures like peroxide value and UV stability are typically superior in oil produced by a modern continuous mill versus an old press, when starting with the same fruit. The ability to crush and extract within hours of harvest, at controlled temperatures, means free fatty acid levels stay extremely low and the positive flavour notes are maximised. Australian producers who have adopted the latest Oliomio systems consistently report better quality and consistency in their oils, even when processing smaller batches. As an example, Spring Gully Olives in Queensland upgraded to a two-phase Oliomio (150 kg/hr) and found it ideal: it allowed them to process their own crop and offer custom processing to neighbouring groves, all while producing oil that needed no further refining - “the 150 kg per hour Oliomio is an ideal capacity which allows small growers to have their own oil processed…and it leaves the oil in its natural state”. This kind of feedback underlines how modern machinery empowers even small-scale growers to achieve high extraction efficiency and premium quality that rivals the big producers.

In summary, the latest Mori-TEM Oliomio systems represent a convergence of advanced engineering and practical on-farm olive oil production. They enable professional, hygienic, and quality-focused extraction at scales from a few dozen kilograms up to several tonnes per hour. By carefully controlling each step - from fruit cleaning and crushing with minimal oxidation, to malaxation under controlled atmosphere, to efficient two-phase centrifuge separation - these machines ensure that the oil produced reflects the true potential of the olives. Australian growers using Oliomio equipment benefit not only from improved oil quality and shelf life, but also from greater independence and flexibility: they can harvest at optimal times and process immediately, rather than rushing to a distant community mill or risking fruit spoilage. The result is fresher, more flavorful extra virgin olive oil that meets the high standards of a sophisticated global market. And with the range of Oliomio models and configurations now available, producers can choose a setup tailored to their grove’s size and business model - whether it’s a one-person boutique press or a regional processing hub servicing multiple farms. The technology has truly opened a new chapter for the industry, one where tradition and innovation blend to produce the finest EVOO. Each bottle of oil pressed with these modern systems tells the story of careful harvest timing, immediate processing, and gentle extraction - a story that resonates strongly with Australia’s drive for quality and the world’s appreciation of premium extra virgin olive oil.

MARKET INSIGHT: GLOBAL OLIVE OIL ECONOMY 2023

Introduction

The global olive oil industry in 2023 has entered uncharted territory, experiencing an extraordinary surge in olive oil prices driven by a combination of climatic and economic forces. At the centre of this crisis lies Spain’s devastating drought, which has crippled the world’s largest olive oil producer. This severe shortage has led to a dramatic contraction in olive oil supply, triggering price escalation and a corresponding decline in consumer demand. The ripple effects are being felt worldwide, reshaping the balance between producers and consumers alike. Meanwhile, Australian olive oil producers find themselves in a rare position of advantage, benefitting from unprecedented market highs. This article explores the causes, consequences, historical trends, and economic signals surrounding this remarkable global olive oil price spike.

The ongoing drought across Spain stands as the principal factor behind the current olive oil price surge. As one of the largest olive oil-producing nations globally, Spain’s drastically reduced harvest - caused by months of extreme heat and minimal rainfall - has sharply curtailed olive oil availability in both European and international markets. This has intensified supply shortages, compelling consumers to pay more for what has long been a staple Mediterranean product. The interplay of limited supply and escalating demand has magnified price volatility, reinforcing the classic supply-and-demand imbalance now driving global markets.

Incredible to see the olive groves of Jaen, Spain. This one province produces around a fifth of the *entire* global supply of olive oil

— Secunder Kermani (@SecKermani) August 31, 2023

But a combination of drought & extreme heat has left many trees badly weakened... This years harvest looks set to be the worst in living memory pic.twitter.com/QYs41eXCwC

As prices have risen steeply, the shortage of olive oil has led to a noticeable decline in consumption, particularly in Spain, where demand has reportedly dropped by around 35%. Consumers are now scaling back their purchases, finding olive oil increasingly unaffordable compared to other cooking oils. The once-steady household consumption patterns are shifting as people seek alternatives or modify their cooking habits. This contraction in domestic demand not only highlights the growing accessibility gap for consumers but also underscores the broader economic strain caused by high inflation and food price increases.

Amid the turmoil, Australian olive oil producers are experiencing a windfall. Thanks to limited global supply, Australian growers are commanding record prices exceeding AUD $8 per litre, marking the highest levels ever recorded in the nation’s olive oil industry. This lucrative period presents a rare opportunity for Australian exporters, with demand from Europe - including Spain itself - now turning toward Australian supplies. For producers Down Under, this unique reversal of roles underscores how regional climate resilience and diversified production can translate into significant financial gains when global shortages arise.

The olive oil market’s volatility is not a new phenomenon. Previous spikes occurred in 1996, 2006, and 2015, each triggered by weather-related supply constraints. Yet, the 2023 price explosion stands out as the most dramatic in recorded history -over 40% higher than any previous price peak, and roughly double the magnitude of earlier surges. This extreme escalation reflects not just climatic hardship but a clear pricing bubble forming within the market, echoing the cyclical nature of commodity pricing.

The olive oil sector has long followed cyclical pricing patterns, typically alternating between low and high price phases roughly every decade. The current surge aligns almost perfectly with the predicted start of another 10-year cycle, occurring just three years into its anticipated timeline. Furthermore, a notable correlation has been identified between the Australian Food Inflation Index and the Global Olive Oil Price Index as reported by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). This connection illustrates the deep interdependence between food commodity pricing and global economic conditions.

While the IMF’s benchmark prices are denominated in USD, for the purposes of this analysis they have been converted to AUD to track the trend relative to Australian markets. These benchmark indicators -based on the world’s largest olive oil exporters -serve as a reliable gauge of overall market direction, confirming how global shortages and inflationary pressures move in tandem.

Global olive oil prices show a recurring 10-year cycle, driven by droughts, crop shortages, and rising production costs

Global olive oil prices show a recurring 10-year cycle, driven by droughts, crop shortages, and rising production costs

From a technical analysis perspective, the Relative Strength Indicator (RSI) is often used to measure price momentum and potential overextension in markets. On recent olive oil price charts, the RSI (represented in purple) indicates that prices have once again entered overbought territory - a level seen during previous speculative phases. Historically, such readings have preceded market corrections or reversals, suggesting that the current surge may not be sustainable in the long term.

Analysts caution that as the European olive harvest begins in September and October 2023, an influx of new oil supplies could help ease prices, though the timing and extent of this correction remain uncertain. Until then, speculative trading and limited inventory continue to support inflated market values.

The record-breaking olive oil prices of 2023, primarily triggered by Spain’s drought-induced production collapse, mark a turning point for the global olive oil economy. With consumer demand declining under the pressure of soaring prices and Australian producers thriving amid the scarcity, the industry is experiencing a dramatic rebalancing. Historical precedents, cyclical trends, and market indicators all point toward a complex, transitional period defined by volatility and uncertainty.

As the world’s producers, traders, and consumers adapt to these new market dynamics, one truth remains clear: olive oil - celebrated for its taste, health benefits, and cultural significance - continues to be at the mercy of both climate change and economic cycles. Stakeholders across the value chain must remain alert, flexible, and forward-thinking as the olive oil market navigates this extraordinary phase of transformation.

Other Sources

Producing high-quality extra virgin olive oil depends not only on fruit quality and processing technology, but also on the strategic use of processing aids - materials added during malaxation or paste handling that facilitate oil release. Although they modify the processing conditions, all approved processing aids share two essential characteristics: they do not remain in the final oil, and they do not negatively affect oil quality.

This article summarises the main categories of processing aids used in olive oil extraction, how they work, and when they offer the greatest benefit.

Processing aids help overcome difficulties such as:

The major classes of processing aids used in olive milling are:

How They Work

Talc is a natural hydrated magnesium silicate with a laminar sheet-like structure. When added to olive paste, it:

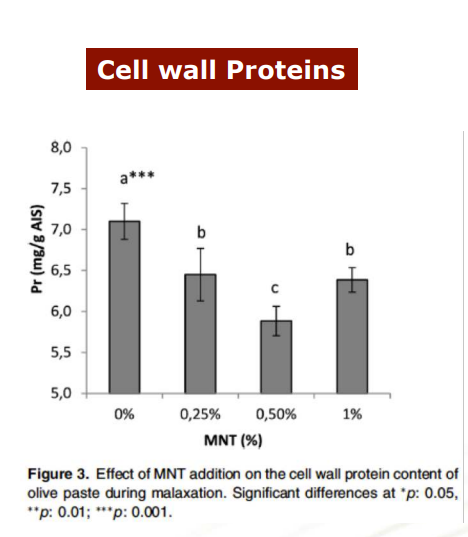

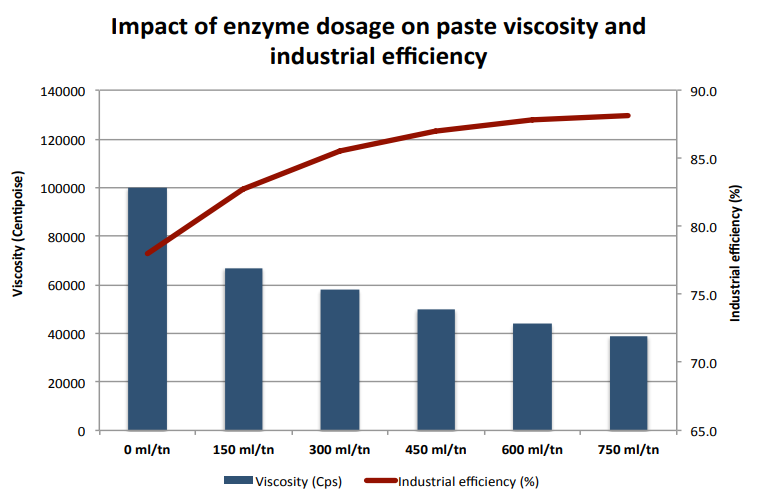

Research presented in the file shows talc:

Total Pectins

Table 3. Effect of talc addition on pectin fractions and total pectin content of olive paste after malaxation

| 0 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WSP (mg/100 g AIS) | 434 ± 59a* | 293 ± 39b | 244 ± 51b | 261 ± 26b |

| CSP (mg/100 g AIS) | 359 ± 35a | 236 ± 11b | 220 ± 7b | 354 ± 4a |

| NSP (mg/100 g AIS) | 483 ± 61ab | 387 ± 55b | 348 ± 23b | 590 ± 62a |

| TP (mg/100 g AIS) | 1275 ± 83a | 915 ± 76b | 812 ± 76b | 1206 ± 88a |

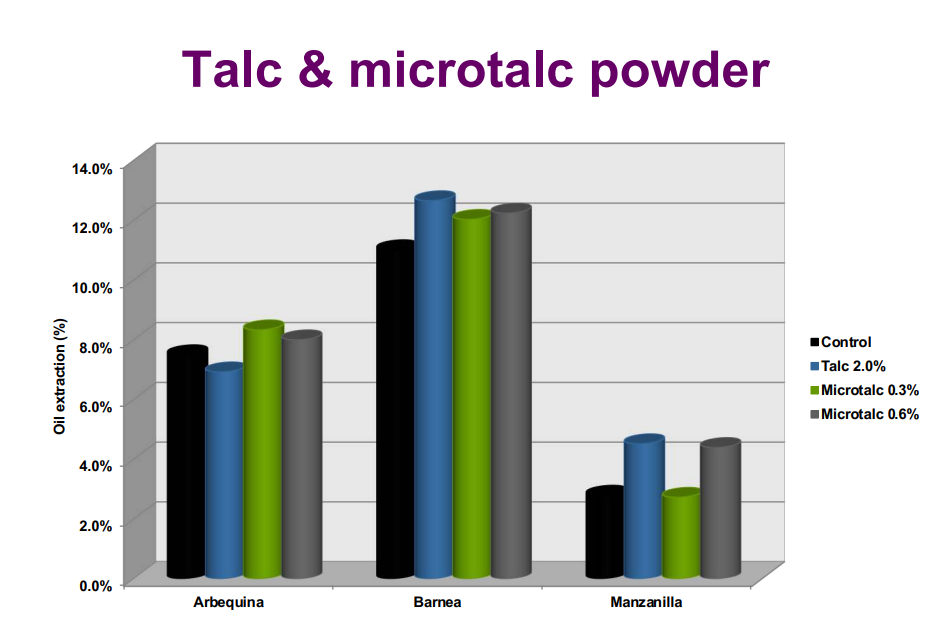

Graphs demonstrate substantial extractability improvements across varieties such as Arbequina, Barnea, and Manzanillo when talc or microtalc is added.

Talc trial in Manzanillo fruit with 61.1% moisture and 3.1 M.I.

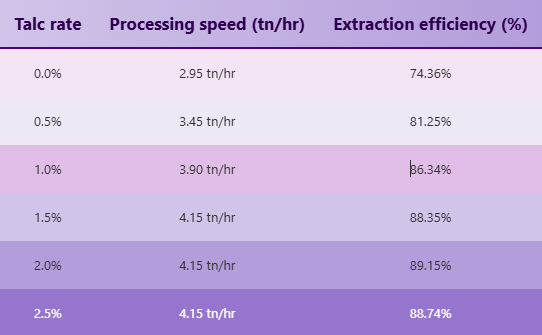

A detailed trial in Manzanillo fruit (61% moisture) shows extraction efficiency rising from 74.36% (no talc) to 89.15% at 2.0% talc.

When to Use Talc

Suggested when:

Mechanism

1–3%, added during malaxation.

Mechanism and Use

A natural calcite mineral with very fine particle size (d50 = 2.8 µm). Its mode of action is similar to talc - promoting aggregation via adsorption.

Benefits

However, CaCO₃ may:

| Salt (NaCl) | Calcium Carbonate |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 4. Comparative effects of Salt (NaCl) and Calcium Carbonate on olive paste extractability, stability, and quality.

Citric acid acts both as a processing aid and a quality modifier:

Mechanism

Documented Effects

Research data shows:

Application

Role in Extraction

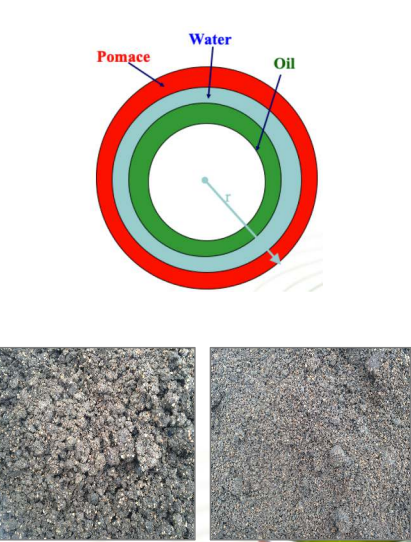

Enzymes (typically pectinases and cellulases from Aspergillus spp.) break down:

This releases oil trapped within cell structures more efficiently.

Key Benefits

Changes in Texture, Total Pectins (TP), and Pectin Esterification Degree in Fruits During Ripening of Olives

| Ripeness Stage | Harvest Date | Texture (N/100 g of fruits) | TP (mg GA/100 g dry wt) | Degree of Esterification (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ripe-green | 11/30/98 | 3889.6 ± 155.3 | 1678.6 ± 72.2 | 63.30 |

| Ripe-green | 12/7/98 | 3023.5 ± 140.7 | 1464.3 ± 60.0 | 65.34 |

| Small reddish spots | 12/14/98 | 2537.2 ± 108.8 | 882.4 ± 41.5 | 44.12 |

| Turning color | 12/21/98 | 2428.4 ± 112.4 | 852.9 ± 38.4 | 42.42 |

| Turning color | 12/28/98 | 2394.7 ± 98.2 | 823.5 ± 41.1 | 40.88 |

| Purple | 1/4/99 | 2253.6 ± 112.9 | 789.5 ± 31.3 | 27.39 |

| Purple | 1/11/99 | 2260.5 ± 90.4 | 763.2 ± 32.2 | 27.59 |

| Black-1 | 1/18/99 | 2119.7 ± 97.9 | 680.5 ± 36.0 | 23.39 |

| Black-2 | 1/25/99 | 1358.3 ± 57.8 | 580.8 ± 25.0 | 24.21 |

| Ripe-black | 1/29/99 | 1027.6 ± 52.5 | 510.6 ± 21.4 | 12.03 |

*Black-1: fruits with black surface and white pulp; Black-2: fruits with black surface and purple pulp; GA: galacturonic acid.

Dosage

A combined approach often yields the best results.

Advantages

Talc and Microtalc

Processing aids are an essential - yet often underused - tool for olive oil producers aiming to optimize extraction efficiency, improve oil yield, and adapt to seasonal and varietal challenges. When applied correctly:

Esterification is a natural chemical reaction where free fatty acids (FFA) combine with alcohols, typically glycerol, to form esters. This process reduces the measurable acidity of the oil. While esterification can occur in the olive paste during milling, it is usually a minor contributor to quality changes compared with factors such as fruit condition, malaxation parameters, and extraction efficiency.

This diagram outlines the continuous olive oil extraction line: olives are crushed, malaxed, separated, clarified, and routed for bottling, while husk and wastewater are channelled to waste management systems.

Processing aids act physically or chemically on the olive paste. Some enhance enzyme activity, others alter pH or moisture, and a few influence esterification indirectly. Below is a breakdown of the main aids used by professional olive processors and how each relates to esterification.

Calcium carbonate is the processing aid most associated with apparent esterification effects.

Influence on esterification

Salt acts primarily on the physical structure of the paste rather than the oil chemistry.

Influence on esterification

Talc is inert and valued for its physical functionality.

Influence on esterification

Commercial enzyme blends can influence chemistry indirectly.

Influence on esterification

These clay minerals are used more for paste modification or clarification.

Influence on esterification

| Processing Aid | Impact on Esterification | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Calcium Carbonate | Moderate … via pH shift | Can lower measured FFA but may affect flavour and oxidation |

| Salt (NaCl) | None | Improvements come from better separation, not chemical change |

| Talc | None | Purely physical aid for difficult pastes |

| Enzymes | Minor, indirect | Mostly physical… chemical breakdown of cell walls |

| Kaolin | None | Improves rheology only |

| Bentonite | None | Used for clarification rather than extraction |

Professional olive mills benefit from:

Esterification occurs when free fatty acids (FFA) in olives or olive paste react with natural alcohols—most commonly glycerol—to form esters. While this is a natural chemical reaction found in many biological systems, it usually plays only a small role during standard olive oil extraction. However, under certain processing or fruit-quality conditions, esterification can become more noticeable and can affect how acidity is interpreted during quality assessment.

Understanding when and why esterification occurs is important for mill operators, as it can influence extraction decisions, processing aid use, and the accuracy of acidity readings that determine Extra Virgin classification.

Esterification is not inherently harmful, but it becomes more noticeable when fruit quality is compromised or when additives alter the paste’s pH and reaction environment. This means that an oil’s reduced measurable acidity may not always reflect true quality improvement.

1. Higher Paste Temperatures

4. Extended Contact Time

5. Enzymatic Activity

When esterification occurs under the conditions described above, it can lower the measured FFA without actually improving the oil’s true chemical quality. This can mislead producers into thinking their processing steps or additives improved the oil, when in reality the acidity reduction was simply a chemical conversion—not a restoration of fruit integrity.

Producers who understand these mechanisms can:

In simple terms: Esterification becomes noticeable when the olive paste is warm, slightly alkaline, contains damaged fruit components, or sits too long before separation. Managing these factors helps prevent misleading acidity readings and supports genuine quality improvements.

Valuing your olive oil processing machinery – from presses and decanters to tractors and harvesters – is an important task for Australian producers. Whether you’re a small boutique grove or a commercial olive operation, knowing what your equipment is worth helps with insurance, resale, and financial planning. This guide explains how to value used olive oil processing machinery (with notes on new equipment costs), covers multiple valuation methods, and offers a practical Australian context. We’ll also include example scenarios (like a decade-old olive press vs. a nearly new separator) and provide tips to maintain your gear’s value over time.

Olive oil production involves specialised machinery at harvest and processing time. Key processing equipment includes olive crushers or mills (to crush olives into paste), malaxers (which slowly mix the paste), and centrifugal decanters/separators (which separate oil from water and solids). Supporting items like pumps, olive washers, and filtration units are also part of the system. Many Australian groves also use standard farm equipment such as tractors, mechanical harvesters, pruning and spraying equipment, and irrigation systems. When assessing value, focus first on the core olive oil machinery, but remember that methods discussed here apply to your tractors, harvesters, and other farm gear as well.

Modern olive processing machinery is a significant investment. For reference, a small continuous-flow olive mill (e.g. 30 kg/hour throughput) might cost around A$20,000 new, while a large commercial plant (capable of ~1 tonne/hour) can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. Such figures underscore why proper valuation is essential – these assets represent major capital on the farm. Below, we outline several methods to evaluate what these machines are worth, especially as they age or when considering second-hand purchases.

Valuing used farm equipment is not an exact science – it’s often best to use multiple methods to triangulate a reasonable value. Common approaches include using depreciation schedules, comparing recent market sales, calculating value based on income or cost savings, considering insurance replacement cost, and accounting for residual (salvage) value. Each method gives a different perspective:

Depreciation is the loss in value of equipment as it ages. A simple way to estimate a used machine’s value is to start from its original cost and subtract depreciation. There are two main depreciation methods: straight-line (also called prime cost) and declining-balance (diminishing value). Straight-line depreciation assumes the asset loses value evenly over its useful life, while declining-balance depreciation assumes a higher loss in early years and less in later years.

For instance, if a small olive press was purchased new for $30,000 and has a 15-year life, straight-line depreciation would be ~6.67% per year (100/15). After 10 years (two-thirds of its life), it would be about 10 × 6.67% ≈ 66.7% depreciated. In simple terms, its book value might be roughly 33% of the original cost (around $10,000 in this example). This assumes no residual value; in practice, you might add a small salvage value (see Residual Value section) instead of depreciating to zero.

Example (Depreciation Method): You bought an olive mill for $100,000 new, which is now 10 years old. Using straight-line (15-year life), its book value would be roughly $100k × (5/15) = $33k remaining. Using diminishing value (13.33% yearly), its book value might be closer to $24k–$25k after 10 years. You could cite these as a range – perhaps saying the machine is “approximately $25k–$33k based on age” – then adjust up or down for condition. If your equipment’s been exceptionally well maintained or lightly used, it might fetch more than the book value; if it’s in rough shape, it could be less.

One of the most practical valuation methods is to see what the market is willing to pay for similar equipment. Check recent listings and sales of comparable olive oil machinery or farm equipment. In Australia, useful platforms include:

Example (Market Comparison): Suppose you own a 10-year-old press (same as above) and find two similar presses listed: one in NSW for $40k (fully serviced, ready for work) and one in SA for $30k (sold as-is, needs some repairs). If your machine is in good working order with maintenance records, the market approach might suggest a value in the high $30k’s. You’d then cross-check this against the $24k–$33k depreciation estimate – if the market seems to be paying a premium (perhaps due to a shortage of used presses), you might lean toward the upper end of the range. On the other hand, if no one is buying presses because many olive groves use custom processing services, you might have to price on the lower end to attract interest.

Another angle is to value equipment based on the income it produces or the savings it provides. This method essentially asks: How much is this machine worth to my farm’s profitability? There are a couple of ways to think about it:

Example (Income Approach): Consider a recently purchased separator (centrifuge) that cost $15,000 new and is only 2 years old. Depreciation might put it at $10k–$12k book value now. But you bought it to improve your oil quality and yield – and indeed, oil yields went up 5%, earning you an extra $5,000 in oil sales each year. If we assume it has at least 8 years of life left, that’s potentially $40k additional income coming. Even discounting future years, the value-in-use of that separator might be on the order of $30k. Of course, no one would pay $30k for a used unit when a new one is $15k, but this tells you that for your own insurance, you might want it covered for replacement cost, and that selling it would only make sense if you exit the business or get a bigger unit. In other words, the ROI approach here tells you the separator is “worth more to me on the farm than to anyone buying it,” so you’d hold onto it unless necessary.

From an insurance perspective, valuation is about ensuring you could replace the equipment if it’s damaged or lost. There are two main concepts used by insurers:

Where to find replacement costs? Contact dealers or check current price lists for the closest equivalent new model. For instance, if your 2008 olive mill is no longer sold, find the price of the current model with a similar capacity. Don’t forget to include freight to your location and installation costs in the replacement figure, as a new machine often involves these. In Australia, companies like The Olive Centre or Olive Agencies can provide quotes for new machinery. We saw earlier that small Oliomio units started around $19.5k a few years back – those prices can guide insurance values for hobby-scale equipment. For larger systems, get a formal quote if possible, since custom setups vary widely.

Also, consider partial loss scenarios: insurance may cover repairs. If you have an older machine, parts might be scarce, so even repairs could approach replacement cost. This is another reason some farmers insure older critical items for replacement cost if they can.

Tip: Document your equipment’s details (serial numbers, specs) and keep evidence of its condition. In an insurance assessment, having maintenance logs, photos, and appraisals can support your valuation. Insurers might depreciate based on a generic schedule, but if you can show your press was fully refurbished last year, you have a case for a higher value. As one farm insurer explains, typically anything over ~8–10 years might only get ACV coverage. If your gear is older but in mint condition or has an ongoing role generating income, discuss options with your insurer – you might opt for a higher agreed value or a policy rider for replacement.

No matter which method you use, don’t forget that machinery usually has some residual value at the end of its useful life. This could be as spare parts, scrap metal, or a second life in a lower-intensity setting. Incorporating residual value prevents undervaluing the asset (and avoids over-depreciating on paper).

When valuing for sale, you might actually set your asking price near the salvage floor if the item is very old. This makes the offering attractive to bargain hunters while ensuring you recover at least scrap value. On the flip side, if you’re buying used equipment, be wary of prices that are at or below typical scrap value – it could indicate the machine is only good for parts.

In summary, always account for the “leftover” value. For insurance, that might not matter (since a total loss is a total loss), but for appraisals and decisions like trading in vs. running to failure, knowing the salvage value helps. For example, if a decanter’s internals are shot, it might still have a salvage value of $5,000 for the stainless steel. That $5k is effectively the bottom-line value no matter what.

Example (Residual Value): You have a 15-year-old tractor that’s been fully depreciated on your books. However, it still runs and could be a backup or sold to a small farm. Checking online, you see similar 80 HP tractors from the mid-2000s selling for around $15,000. That’s the residual market value. Even if you only get $10k due to some issues, that’s far above scrap metal value (maybe a few thousand). Therefore, in your valuation, you wouldn’t list the tractor as $0 – you’d acknowledge, say, a $12k residual value in fair condition. This logic applies to olive equipment too: an old olive washer or oil storage tank might be fully written off in accounts, but it has residual usefulness that someone will pay for.

Each method has its strengths. The table below summarises and compares these approaches:

Each method yields a piece of the puzzle. In practice, when preparing a valuation (for example, for a financial statement or an insurance schedule), you might list multiple figures: “Depreciated value: $X; Likely market value: $Y; Replacement cost: $Z.” This gives a range and context rather than a single uncertain number

Let’s apply the above methods to two concrete scenarios to see how they complement each other:

Scenario 1: Valuing a 10-Year-Old Olive Oil Press

Background: You purchased a medium-sized olive oil press (continuous centrifugal system) 10 years ago for $100,000. It has been used each harvest, processing around 50 tonnes of olives per year. It’s well-maintained, though out of warranty now. You are considering upgrading to a newer model and want to determine a fair sale price or insurance value.

Scenario 2: Valuing a Nearly New Separator (Centrifuge)

Background: You bought a new centrifugal separator (vertical centrifuge for polishing oil) 1 year ago for $20,000. It’s a high-speed clarifier that improves oil quality. Unfortunately, you’re now restructuring your operations and might sell this unit. It’s in “as-new” condition. How to value it?

Valuing farm equipment in Australia comes with some local considerations that can affect prices and depreciation. Here are a few factors particularly relevant to Aussie olive producers:

Depending on your goal – insuring the asset, selling it, or accounting for it – you’ll approach valuation with a slightly different mindset and requirements. Here’s how to handle each:

By implementing the above steps, you not only retain the value of your olive oil machinery but can enhance it relative to similar-aged units on the market. A well-maintained 15-year-old olive press could outperform a neglected 10-year-old press, and its value would reflect that. Many buyers would rather pay more for the former, knowing it was cared for. Good maintenance is like money in the bank for equipment value.

Specialised machinery like over-the-row olive harvesters can hold their value well if maintained, though hours of use and local demand are key factors. For instance, the Colossus harvester pictured (built in Mildura, VIC) had logged about 7,735 hours – yet with components rebuilt and good upkeep, it remains a sought-after asset for large groves. When valuing such equipment, consider service history (e.g. newly rebuilt conveyors or engines), as major refurbishments can extend useful life significantly. Heavy machinery also benefits from many of the tips above: regular cleaning (clearing out olive leaves and dust), timely engine servicing (as per John Deere engine schedules in this case), and storing under cover in off-season all help preserve value. Usage hours are akin to mileage on a car – they directly impact value, but how those hours were accumulated (easy flat terrain vs. rough use) also matters. Keeping detailed records (hours of use per season, any downtime issues resolved) will support a higher valuation when selling to the next operator.

Finally, don’t underestimate the value of operational knowledge and support documents. If you’re handing off a complex piece of gear, providing training to the buyer or passing along your notes (like ideal settings for different olive varieties, or a log of any quirks in the machine and how to manage them) can make your item more attractive, thereby supporting your asking price. It’s not a tangible “value” in dollars, but it eases the sale and might tip a buyer to choose your machine over another.

Valuing olive oil processing machinery and farm equipment requires blending hard numbers with practical insight. By using depreciation formulas, checking market prices, considering the machine’s contribution to your farm, and factoring in replacement costs, you can arrive at a well-supported valuation range. Always adjust for the realities of the Australian market – our distances, climate, and industry size mean context is key. And remember, the way you care for and present your equipment can significantly sway its value.

Whether you’re insuring your olive press, selling a used tractor, or just updating your asset register for the accountant, a thoughtful valuation will pay off. It ensures you neither leave money on the table nor hold unrealistic expectations. Use the following checklist as a guide whenever you undertake a machinery valuation:

Valuation Checklist for Olive Machinery & Farm Equipment:

Valuing farm equipment is part art and part science. The science comes from formulas and data; the art comes from experience and understanding of how your machinery fits into the bigger picture. With the guidelines above, you have tools from both domains at your disposal. Happy valuing – and may your olive machinery serve you efficiently and profitably throughout its life!

Sources

CONSUMER EDUCATION

Extra Virgin Olive Oil (EVOO) is often hailed as a “liquid gold” in kitchens around the world – a term famously used by the ancient Greek poet Homer. For Australians, EVOO is more than just an ingredient; it’s a heart-healthy cooking staple and a link to centuries of Mediterranean tradition. This guide will explain exactly what EVOO is and how it differs from other olive oils, how it’s produced (from grove to bottle), its science-backed health benefits, and the many ways you can use it – both in your cooking and beyond. Along the way, we’ll share some interesting facts that highlight why this oil has been prized since antiquity. Let’s dive in!

By contrast, other grades of olive oil are lower in quality or more processed:

In summary, EVOO stands apart from other olive oils because it’s unrefined, of top sensory quality, and packed with natural compounds. If you drizzle a good EVOO on a salad or taste it on a spoon, you’ll notice a bright, complex flavour – something you won’t get from the flat, one-note taste of refined “olive oil” blends.

EVOO’s journey from tree to bottle is a fascinating combination of ancient tradition and modern food science. It all starts in the olive groves. Olives destined for high-quality EVOO are often hand-picked or gently shaken off trees (modern farms may use mechanical harvesters that vibrate the trunks or use catching frames). The timing of harvest is crucial: early in the season, when olives are green to purplish, they yield less oil, but it’s very rich in flavour and antioxidants; later harvest (ripe black olives) yields more oil but with mellower taste. Many premium Australian producers, much like those in the Mediterranean, opt for early harvest to maximise quality.

Once picked, speed is key – olives are quickly transported to the mill, because freshly harvested olives start to oxidise and ferment if they sit too long. Ideally, olives are pressed within 24 hours of harvest to prevent quality loss. At the mill, the olives are washed to remove leaves and dust, then crushed (pits and all) by either traditional stone mills or modern steel crushers. This creates an olive paste, which is then gently malaxed (slowly churned) for 20–45 minutes. Malaxation allows tiny oil droplets to coalesce, but it’s done under strict temperature control – this is where the term “cold-pressed” or “cold extraction” comes in. To qualify as cold-pressed, no heat above 27 °C is applied during extraction. Keeping the paste cool preserves aromatic compounds and nutrients; higher temperatures could extract a bit more oil, but at the cost of flavour and antioxidants. Australian and European producers alike adhere to this, as heat can reduce EVOO’s polyphenols and vitamin E (and increase oxidation)

A Roman-era olive oil press in Capernaum, Israel. Ancient presses used large millstones to crush olives, and the oil was separated by gravity. Today, modern cold-pressing uses centrifuge extractors, but the goal remains the same – to physically squeeze oil from olives without chemicals or high heat, preserving quality. (photograph of a Roman-era olive mill in Capernaum)

After malaxation, the paste is pressed or, more commonly, centrifuged. Modern mills use a decanter centrifuge, which rapidly spins the olive paste to separate oil from water and olive solids. The result is fresh olive oil (plus some vegetable water). The oil may then be filtered or simply left to settle so that tiny particles and moisture drop out over time. Some artisan oils are unfiltered, yielding a cloudy appearance, but most commercial EVOOs are filtered for clarity and stability. Finally, the oil is stored in stainless steel tanks (ideally with minimal air exposure) and later bottled.

Throughout production, maintaining quality is paramount. At no point are solvents or refining used – EVOO is purely a natural juice. This careful process explains why EVOO is more expensive than generic cooking oil: it takes a lot of olives and care to produce. In fact, it typically takes around 4 to 6 kilograms of olives to cold-extract just 1 litre of EVOO (for some early harvest oils, even more). That represents roughly 8000–10,000 individual olives in each litre of premium oil! Such figures help us appreciate the effort and agricultural value inside each bottle of EVOO.

Australian EVOO note: Australia may be far from the Mediterranean, but it has a burgeoning olive oil industry of its own. Olives were first brought to Australia in the 1800s, and the industry remained small until a boom in the late 20th century. The Australian olive industry is over 150 years old, but it has expanded rapidly across all mainland states in recent decades. Today, Australia produces high-quality EVOOs, particularly in regions with Mediterranean-like climates (such as parts of South Australia, Victoria, and Western Australia). Aussie EVOOs often win awards for their robust flavours and purity, thanks to modern farming and milling techniques. So when you shop, know that some EVOO on the shelf – in addition to imports from Italy, Spain, Greece, etc. – is grown and pressed right here in Australia.

Extra Virgin Olive Oil isn’t just a tasty fat – it’s exceptionally good for you. Its health benefits are backed by a wealth of scientific research and have even been recognised by international health authorities. Here are some of the top evidence-based benefits:

Lastly, remember that EVOO is a fat and thus calorie-dense, so use it in place of other fats rather than simply adding on (to balance overall energy intake). But as fats go, EVOO is about the best you can choose for your health. It’s no surprise the Australian Dietary Guidelines and Heart Foundation include olive oil as a core part of a healthy eating pattern, encouraging people to swap butter and animal fats for olive or other plant oils. EVOO isn’t a miracle cure-all, but it is a potent, natural contributor to wellness – and a delicious one at that!

One of the beauties of EVOO is its culinary versatility. You can use it raw, you can cook with it, you can even bake with it. Here are some popular ways to integrate EVOO into your daily diet, along with tips particularly suited for Australian kitchens:

Drizzling extra virgin olive oil over a salad of avocado, tomato, and greens. Incorporating EVOO into daily meals can be as simple as using it to dress salads, dip bread, or finish cooked dishes – adding both flavor and healthy fats to the Australian diet.

Quick recipe ideas:

Olive oil’s usefulness goes far beyond food. Throughout history, olive oil has been used in daily life in myriad ways – and many of these uses are still relevant or just plain handy today. Here are some nonculinary applications of olive oil:

As you can see, a bottle of olive oil in the cupboard can double as a mini home remedy kit! One caveat: for non-food uses, you don’t necessarily need to use your finest extra virgin oil – a basic grade or older bottle that you don’t want to cook with can find a second life polishing your coffee table or deep-conditioning your hair. Food-grade olive oil for beauty and home use means you’re avoiding the petrochemicals found in some commercial products, which is a win for those with sensitive skin or who prefer eco-friendly options.

To round out our EVOO guide, here are some fun facts and bits of trivia that make olive oil even more fascinating:

Extra Virgin Olive Oil is truly a kitchen all-star – it elevates our food and supports our health. We’ve learned that EVOO differs from lesser olive oils in quality and production, coming straight from fresh olives without chemicals or refining. We’ve seen how it’s made, preserving its sensory and nutritional treasures. Science shows that incorporating EVOO into your diet can benefit your heart, reduce inflammation, and even help you enjoy your veggies more (because they taste better with a good drizzle!). And beyond cooking, olive oil proves its worth in our beauty routines and households.

For Australian consumers, the message is embrace EVOO: use it in your salad dressings, swap it for butter when you can, try it in new recipes – both traditional Mediterranean dishes and local Aussie favourites. With Australian olive oil production on the rise, you might even explore home-grown EVOOs, which can be world-class. Remember to store it well, use it generously but mindfully, and appreciate the story behind it – from ancient olive groves to your dinner table.

In summary, Extra Virgin Olive Oil is more than an ingredient; it’s a lifestyle choice towards better eating and living. So go ahead – enjoy that splash of liquid gold in your meals every day, and taste the difference it makes!

References (selected):